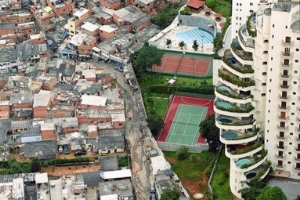

Whenever there are disparities in income, inequities in health are inevitable. Today in the US, the gap between the rich and the poor is much greater than in most other highly developed democratic countries, and so are the health inequities. The roots of this inequality lie deep in the histories of developed nations.

Whenever there are disparities in income, inequities in health are inevitable. Today in the US, the gap between the rich and the poor is much greater than in most other highly developed democratic countries, and so are the health inequities. The roots of this inequality lie deep in the histories of developed nations.

When children in impoverished countries die of famine, dehydration, and HIV/AIDS, the images are shocking and unacceptable, but somehow not unexpected. We understand that there will be health differences between rich and poor countries. It was not that long ago, however, that the gap between the rich and the poor within highly developed nations – Britain, France, Germany, the US — was as appalling as what we now see in third world countries.

The average age of death for the working class was 16

While health inequities between the rich and the poor are timeless, it’s only in recent centuries that we have the statistics to prove it.

For example, a report issued in 1842 in Great Britain found that, in the Bethnal Green area of the East End of London, the average age of death for the working class was 16. Nearby residents who were better off financially lived to be 45.

Similar statistics were collected in France in the early 19th century. The physician Louis René Villermé analyzed Parisian arrondissements (city districts), looking for correlations between death rates and variables such as elevation, soil, weather, or congestion. It was only when he looked at wealth that he found a connection. The annual death rate in one of the poorest districts of Paris was over 30 per 1000. Just across the river on the Île Saint-Louis, affluent residents had a death rate of 19.1 per 1000.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, whenever industrializing nations collected statistics, they found a direct correlation of income with death and disease.

The pestilential human rookeries of early industrial towns

Britain’s population grew from 6 million to 18 million between 1750 and 1850. The population of London went from 800,000 in 1801 to 1,800,000 forty years later. In 1750, only 15 percent of the population lived in towns. By 1880 that number was 80 percent.

Living conditions in industrialized cities were deplorable and extremely unhealthy. Roy Porter, in The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, describes it like this:

[F]oul housing, often in flooded cellars, gross overcrowding, atmospheric and water-supply pollution, overflowing cesspools, contaminated pumps; poverty, hunger, fatigue and abjection everywhere. Such conditions, comparable to today’s Third World shanty towns or refugee camps, bred rampant sickness of every kind. Appalling neo-natal, infant and child mortality accompanied the abomination of child labour in mines and factories; life expectations were exceedingly low – often under twenty years among the working classes – and everywhere sickness precipitated family breakdown, pauperization and social crisis.

Friedrich Engels documented these conditions in his The Condition of the Working Class in England. A less well known account, quoted by Porter, is from Andrew Mearn’s Bitter Cry of Outcast London, a pamphlet published in 1883. He describes visiting the “pestilential human rookeries … where tens of thousands are crowded together amidst horrors which call to mind what we have heard of the middle passage of the slave ship.”

To get to them you have to penetrate courts reeking with poisonous and malodorous gases arising from accumulations of sewage and refuse scattered in all directions and often flowing beneath your feet; courts, many of them which the sun never penetrates, which are never visited by a breath of fresh air, and which rarely know the virtues of a drop of cleansing water. … You have to grope your way along dark and filthy passages swarming with vermin. Then, if you are not driven back by the intolerable stench, you may gain admittance to the dens in which these thousands of beings who belong, as much as you, to the race for whom Christ died, herd together.

A common disease that flourished under these conditions was rickets, a softening of the bones that leads to fractures and deformity. Rickets was often fatal for women, who died the first time they gave birth due to their pelvic deformities. For those who survived rickets, there was tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles, chickenpox, smallpox, typhoid fever, typhus, diarrhea, dysentery, and cholera.

Unsafe and unhealthy working conditions

Working conditions in the early days of industrialization were both unsafe and unhealthy. Children worked long hours in a high speed, mechanized factory system. Accidents and mutilations were common.

Chimney sweeps developed scrotal cancer from exposure to soot. Coal miners were afflicted with pneumoconiosis (a lung disease caused by inhaling coal dust). Cotton workers got brown lung disease. Match workers, exposed to phosphorus, developed a necrosis of the jaw called “phossy jaw.” Their bones would actually glow in the dark. Miners, brick-makers, and potters, exposed to dust from stone, flint, and sand, developed silicosis and other lung diseases.

Here is Engels’ description of children employed in glass making:

In the manufacture of glass … the hard labour, the irregularity of the hours, the frequent night-work, and especially the great heat of the working place (100 to 190 Fahrenheit), engender in children general debility and disease, stunted growth, and especially affections of the eye, bowel complaint, and rheumatic and bronchial affections. Many of the children are pale, have red eyes, often blind for weeks at a time, suffer from violent nausea, vomiting, coughs, colds, and rheumatism. … The glass-blowers usually die young of debility or chest infections.

Continued in the next post.

Related posts:

Déjà vu: Historical resistance to the inequities of health

Health inequities, politics, and the public option

Health care inequality: The US vs. Europe

The problem in Afghanistan is hunger

The enduring benefits of saving children

Global warming makes me sick

Sources:

(Hover over book titles for more info. Links will open in a separate window or tab.)

Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity

Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (Oxford World’s Classics)

Andrew Mearns, Bitter Cry of Outcast London

Dorothy Porter, Public Health, in W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter, Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, Vol. 2, p 1231-1261.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.