What’s happened to psychiatry over the last 15 to 20 years? That’s a big subject, discussed in many recent and excellent books. One of those books is by Daniel Carlat, author of Unhinged: The Trouble with Psychiatry – A Doctor’s Revelations about a Profession in Crisis

What’s happened to psychiatry over the last 15 to 20 years? That’s a big subject, discussed in many recent and excellent books. One of those books is by Daniel Carlat, author of Unhinged: The Trouble with Psychiatry – A Doctor’s Revelations about a Profession in Crisis.

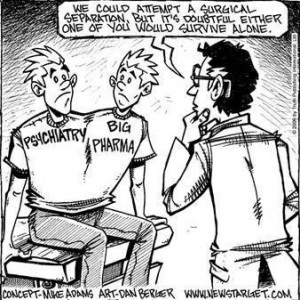

One of the problems Carlat readily acknowledges is that psychiatry is excessively focused on psychopharmaceuticals at the expense of other effective treatments. Not only is there too much focus on drugs as treatment. There’s so much money flowing from the pharmaceutical industry to psychiatrists that it makes one wonder if the profession can be objective.

Evidence of financial ties was documented by clinical psychologist Lisa Cosgrove. She considered those psychiatric experts who were responsible for the diagnostic criteria in the DSM, the bible of psychiatric disorders. Of the 170 psychiatrists who contributed their expertise on mood and psychotic disorders, 100% had financial ties to drug companies.

Carlat asks: Why do psychiatrists take more money from the pharmaceutical industry than other doctors? His answer:

Our diagnoses are subjective and expandable, and we have few rational reasons for choosing one treatment over another. This makes us ideal prey for marketers who are happy to provide us with a false sense of therapeutic certainty, as long as that certainty results in their drug being prescribed. Furthermore, psychiatrists feel inferior and less ‘medical’ than other specialties. Working at high levels with drug companies gives us a sense of power and prestige that is otherwise missing.

The education of a psychiatrist

Part of that sense of feeling inferior starts in med school. Carlat offers a number of reasons why medical school is not good for psychiatrists:

- It creates an excessively biomedical view of problems that actually have many other sources (like conditions of daily life).

- Psychiatrists feel inferior to other doctors. (In the medical school pecking order, only the failures go into psychiatry. See Sandeep Jauhar’s comments in Intern: A Doctor’s Initiation

.)

- Psychiatrists feel superior to other mental health workers because they went to medical school.

- The time and effort spent on medical school could be much better spent on activities directly related to what psychiatrists go on to practice. (They won’t be called on to deliver babies or perform surgery, for example.)

The med school experience explains, in part, why psychiatrists are antagonistic to colleagues in related disciplines, such as psychotherapists or clinical psychologists. What’s also going on there, however, is that psychiatrists feel a need to protect their own turf. Studies that show therapy or cognitive behavioral training is as effective as drugs are not in the interest of psychiatry.

The felt need to be scientific and biomedical – to be more “medical” than thou – is unfortunate. Psychiatry deals with the human condition, the human soul. When psychiatrists feel a need to insist that they are just as “medical” as other MDs, they no longer acknowledge that psychiatry is and should be essentially different from other medical pursuits.

The biological basis of psychiatric disorders

Modern psychiatry seems to believe that every deviation from “normal” can be explained exclusively by neurological activity in the brain and can be treated by drugs that modify that activity – depression being the main disorder that gets treated these days. Carlat, despite offering criticism of his profession on many counts, subscribes to this view wholeheartedly. “How could mental illness not be, ultimately, biological?” he says. And again, “Undoubtedly, there are both neurobiological and genetic causes for all mental disorders.”

It seems to me there’s a distinction between biological effects and biological causes. Childhood abuse and the trauma of combat may have a biological effect on the brain, but should a psychiatrist offer treatment only after the biological damage has been done? If the only tool the psychiatrist has is psychopharmaceutical modification, then the answer is yes.

Something has happened to psychiatry in recent years that’s not good for either practitioners or patients. Something needs to change. The “bar room brawl” (as Carlat calls it) over revising the next edition of the DSM is probably the best thing that could happen to psychiatry.

Update 10/2/10:

Psychiatrists change their recommendations for depression’s treatment (Los Angeles Times)

The American Psychiatric Association, authors of the DSM, released “Practice Guideline for Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder” yesterday, which includes an endorsement of electro-convulsive therapy. Their endorsement of talk therapy is “tepid,” but they’re willing to say physical exercise may have “at least modest” benefit.

On the pharma connection:

The authors of the practice guideline also engaged in a level of self-disclosure that is new for many psychiatrists. The guideline opens with two pages detailing the extensive ties of those who drafted the document with the pharmaceutical industry. Of the work group’s seven members, all but one declared that he or she received research support, consulting payments, speaking fees or author’s honoraria from several firms developing, manufacturing or marketing psychiatric drugs.

The American Psychiatric Assn. sought to counter any appearance of undue pharmaceutical-industry influence by establishing an “Independent Review Panel,” whose five members were free of any direct financial ties to drug companies, and were charged with “identifying any possible bias.” That panel, the APA reports, “found no evidence of bias.”

Related posts:

Should grief be labeled and treated as depression?

Should the medical establishment regulate psychotherapy?

Are some diseases more prestigious than others?

The physician as humanist

Resources:

Image source: Beyond Meds

Shankar Vedantam, Psychiatric experts found to have financial links to drugmakers, Washington Post, April 20, 2006

Daniel Carlat, Unhinged: The Trouble with Psychiatry – A Doctor’s Revelations about a Profession in Crisis

Daniel Carlat, DSM-5’s Rough Draft: The Carlat Take, The Carlat Psychiatry Blog, February 11, 2010

I am certainly not qualified to make an informed comment on this subject here at Health Culture. I felt the same about the previous and great post on grief. But I do have opinions. And I think not only psychiatry, but the medical establishment too, both have a strong preference for the pill route to solve all our problems. It’s so easy and fast and you don’t have to really care about the patient.

My limited knowledge tells me that, yes, often there is a biomedical component of psychological issues. But which came first: the biomedical conditions or the daily life conditions? Life conditions can affect the biomedical condition. To be effective I think it is necessary for treatment to first deal with the daily conditions and if necessary use the meds to help the person function while getting at the daily life issues. The goal should not be a doped out zombie. It is helping people learn to cope with life’s normal ups and downs.

Personal opinion: I believe the entire medical complex relies too much on pills. It is the easy way out. Have a headache. Take a pill. Have a heartache. Take a pill. Have an eating disorder. Take a pill.

That system will be hard to break because of the excessive profits that are being made.

I think a lot of America’s problems these days stems from one thing. GREED.

In my opinion, you don’t need to be an expert to have an opinion on things that strike you as wrong. Greed is what often comes to my mind, too, about many problems. It’s a combination of human nature and the opportunity for financial profit. Whether it’s an individual, a single corporation, or a business interest with a monopoly, there’s no ethical motivation to be responsible for or concerned about the consequences of one’s actions – whether it’s industrial pollution or the deadly side-effects of a pharmaceutical drug. That’s why we need laws and regulations.

But laws and regulations require enforcement, which in turn requires adequate funding. In most cases, that funding is not enough to outsmart and outspend an industry that invests heavily in lobbying Congress, such as the pharmaceutical industry. Fines levied against big pharma companies are calculated into their cost of doing business, ultimately driving up prices. What choice do consumers have? Boycott and die?

Look at how long it took to make any progress with the tobacco industry. I just read an interesting article that compares combating the addictive properties of sugar, fat, and salt with the tobacco industry battle. (It quotes one of your favorite authors on the subject, David Kessler, The End of Overeating .) Turns out there’s a lawyer who thinks there could be enough evidence to sue the fast food industry for knowingly selling food that’s harmful to health. That would be a very difficult case to win, but I wager we’ll be hearing more and more about the addictive properties of junk food.

.) Turns out there’s a lawyer who thinks there could be enough evidence to sue the fast food industry for knowingly selling food that’s harmful to health. That would be a very difficult case to win, but I wager we’ll be hearing more and more about the addictive properties of junk food.

The complete article on this (at Junkie food: Tastes your brain can’t resist) isn’t available online, unfortunately. It’s in New Scientist and I read the library’s copy. I love reading New Scientist. In addition to information that relates to health and medicine, it has cool stories like how our whole universe could actually be inside a black hole and we wouldn’t know it!

Thanks for your comment, Roberta.

“how our whole universe could actually be inside a black hole and we wouldn’t know it!”

That would explain a lot, wouldn’t it?

Thanks, Roberta. I tend to be a very literal-minded person and completely missed the humor in that.

Disagree with this post in that it buys into the usual psychiatry bashing – that they are pill-pushing servants of Big Pharma – ignoring the fact that most psychiatrists do psychotherapy as part of their daily practice, and when issues in medication treatment come up, psychiatrists tend to be referred only cases where medication treatment has already been tried and failed or is too complicated for primary care.

85% if psych meds in the US are prescribed by Non-psychiatrists (primary care docs, Nurse practitioners, PAs, etc.). Psychiatrists only prescribe 15% of psychiatric medications in the United States. People blame psychiatrists for prescribing meds, not realizing that to get into a psychopharmacologist psychiatrist’s office, usually you’ve already tried medications (Rx’d by other providers), often multiple ones, and the psychiatrist is usually brought on as the last resort to deal with complicated cases. But because the psychiatrist is holding the hot potato, they get the blame from the public for over-prescribing, when the chain of events started way downstream from their office. Yet they get all the blame for the overuse of medications in treatment of mental illness. Why? Because psychiatrists are an easy target. Most people who bash psychiatrists have never even met one. Fewer still have had to utilize their services. It’s easy to stereotype and dump on people you don’t know.

Thanks so much for offering this perspective. I certainly got the impression from Carlat’s book that – after the initial visit — psychiatrists primarily do 15-minute visits to adjust the patient’s medication. I’ve also heard wonderful reports of psychiatrists who do monthly hour-long sessions where they primarily listen to the patient.

In the health system I’m familiar with (Kaiser), primary physicians refer to psychiatrists rather than prescribe themselves, and it’s not difficult for patients to see psychiatrists, even without a referral.

There does seem to be evidence of a close relationship between psychiatrists and the pharmaceutical industry – more than just the few bad apples who’ve gotten all the publicity.