Movies in which life is all the more precious because the main character has a fatal disease are common Hollywood fare. Love Story and Terms of Endearment

come to mind. Jenny (Ali MacGraw), in Love Story, appears to have leukemia. Emma (Debra Winger), in Terms of Endearment, has an incurable cancer.

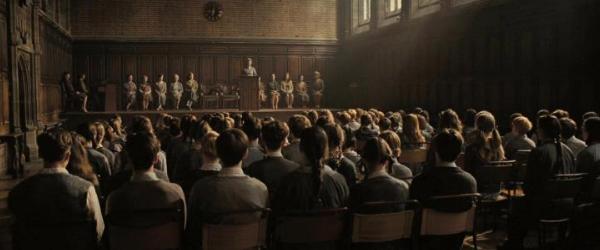

Never Let Me Go, a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro, has been turned into a film

that’s a variation on this theme. The director, Mark Romanek, asserts he was making a love story. In the final scene, the surviving character, Kathy H. (Carey Mulligan), says: “Maybe none of us really understands what we’ve lived through, or feels we’ve had enough time.” Romanek comments: “Since our lives are so short, it makes you change perspective about what’s important.”

The movie trailer (below) has a voice-over that says “Love made them human.” But there’s nothing about the characters that suggests they’re anything less than human. They don’t need a love story for that. The premise of the film is so much more than a character’s brief life and death. (If you haven’t seen the film or read the book, insert spoiler alert here.)

Romanek: “I wasn’t making a sci-fi”

The story takes place in the recent past, but Ishiguro has reimagined a few things. Medical breakthroughs have increased the average lifespan to 100 years, creating a huge demand for body parts that can be transplanted from the young and healthy. A segment of the population – their parentage only vaguely alluded to – has been designated from birth to become organ donors.

The reality of the donors’ lives – the truncated future they face – is revealed only gradually to them (and to the viewer) as they mature from child to adult. The film is so visually and acoustically lush – and the plot so concentrated on the love story – that one can easily fail to register moral repulsion at the premise. That would be a lost opportunity in the face of current organ shortages, rationing (kidneys for the young, not the old), and – more important – the immorality of exploitation.

A review in The Lancet finds the characters’ passive acceptance of their fate disturbing, though understated.

[T]he romantic drama works despite the film’s sensational premise. In large part that’s because the film’s moral universe is not so very much unlike our own. Faced with our own organ crisis, we too continue to enlarge the pool of potential donors. Meanwhile, a black market in organs thrives. The demands of medical progress are indeed unstoppable, even as they deepen the possibility of exploitation. We know all this, but like the protagonists of Never Let Me Go, for the most part we accept it, too. That – not the coerced surgeries and farming of human beings – may be the film’s most chilling aspect.

Joseph O’Neill, in his review of the novel in The Atlantic, identifies a larger theme. (emphasis added)

[The children’s] hesitant progression into knowledge of their plight is an extreme and heartbreaking version of the exodus of all children from the innocence in which the benevolent but fraudulent adult world conspires to place them. We grow up — if we’re lucky — in security and wonder, and afterward are delivered to the grotesque fact of our end. And then? Ishiguro’s dark answer is that the modern desperation regarding death, combined with technological advances and the natural human capacity for self-serving fictions and evasions (look no further than our see-no-evil consumption of animals), could easily give rise to new varieties of socially approved atrocities; one of the many Nietzschean insights of the novel is that successful crimes produce mutations in morality.

The acquiescence of the weak to the strong

David Cox in The Guardian finds political and social commentary. (emphasis added)

[O]ur doomed heroes find their fate dictated not by implacable forces that are beyond their power to influence, but by the designs of their fellow human beings. … If this is a celebration of love, why don’t the protagonists assert its power by rebelling against those intent on thwarting it? … The main characters’ fate isn’t merely to die; it’s also to live as the mere instruments of others.

Their condition hints at the wider exploitation of the many by the few that we every day take for granted. … Our young unemployed don’t besiege the hedge-fund offices of Mayfair. For the most part, our children accept the role in life they’re accorded as uncomplainingly as the students of Hailsham.

The lackeys of capitalism compete to become employee of the month, just as the donors of Never Let Me Go take a pride in their donations. In both cases, the system has indoctrinated them so successfully that they’ve ended up perfectly willing to accept their part in an apparently unalterable scheme of things. …

It’s the acquiescence of the weak in their own exploitation by the strong.

This, I find, is what makes the film so disturbing.

The admonitions and premonitions of this beautifully executed film are an opportunity to project a variety of interpretations – despite the director’s intent to present a love story. That’s what makes Ishiguro’s tale a work of art.

Related posts:

Grey’s Anatomy donates a body to medicine

Knowing when you’ll die: Tony Judt’s last interview

Atul Gawande: Modern death and dying

Actions surrounding the moment of death are highly symbolic

Ich Habe Genug on Thanksgiving

Resources:

Image: FilmoFilia

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Sonia Shah, Dark harvest, The Lancet, February 12, 2011

Joseph O’Neill, New Fiction – Finds and flops, The Atlantic, April 5, 2005

David Cox, How Never Let Me Go gave up and died, The Guardian, February 14, 2011

Manohla Dargis, Growing Up in a Hush, With the Ultimate Identity Crisis, The New York Times, September 14, 2010

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.