[This post contains links to the New York Times. If you position your mouse over a link, you can view the destination URL at the bottom of your browser.]

[This post contains links to the New York Times. If you position your mouse over a link, you can view the destination URL at the bottom of your browser.]

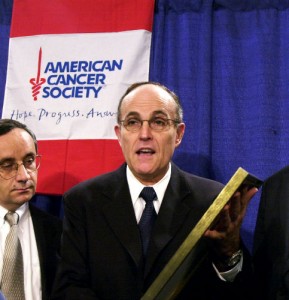

When former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani was seeking the Republican presidential nomination in 2007, he used to give a campaign speech that referred to prostate cancer and health care. His sound bites were turned into a radio commercial and included the following:

I had prostate cancer five, six years ago. My chance of surviving prostate cancer — and, thank God, I was cured of it — in the United States? Eighty-two percent. My chance of surviving prostate cancer in England? Only 44 percent under socialized medicine.

What’s wrong with this picture? Several things.

The numbers themselves – the 82 and 44 percent — were incorrect. Chances of survival are typically stated as the prospect of living another five years. According to the National Cancer Institute, the five-year survival rate for prostate cancer in the US is 98.4%. For England (according to the United Kingdom’s Office of National Statistics), the number is 74.4%.

Where did the lowly 44% for England come from? Giuliani’s health care adviser started with the number of people who have prostate cancer and the number who die (called incidence and mortality rates): how many people have the disease in a given year and how many die from the disease in that year. From those numbers he came up with a five-year survival rate. This is not possible. “Five-year survival rates cannot be calculated from incidence and mortality rates, as any good epidemiologist knows,” according to the Commonwealth Fund.