This post became much too long, so I’ve divided it into two parts. The first part is mainly about neoliberalism; the second mainly about graphic warnings on cigarette packs (plus smoking among the homeless). When I read, in a recent NEJM article, “The Supreme Court’s increasing sympathy for corporate speech and decreasing deference to public health authorities makes it more difficult for government to protect the public’s health,” my first thought was: What a perfect example of neoliberalism in action.

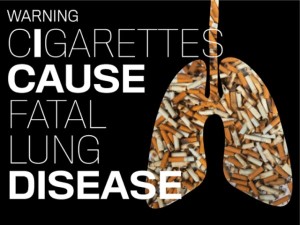

No one would claim that neoliberalism strives for consistency when implementing its ideals. For example, neoliberalism blames individuals for the health consequences of cigarette smoking (“I cause disease”) and at the same time opposes legislation to reduce cigarette consumption (graphic warnings on cigarette packs). When there is a choice to be made, the deciding factor for neoliberalism will be the efficiency with which wealth can be upwardly redistributed.

No one would claim that neoliberalism strives for consistency when implementing its ideals. For example, neoliberalism blames individuals for the health consequences of cigarette smoking (“I cause disease”) and at the same time opposes legislation to reduce cigarette consumption (graphic warnings on cigarette packs). When there is a choice to be made, the deciding factor for neoliberalism will be the efficiency with which wealth can be upwardly redistributed.

Personal responsibility

Personal responsibility — including personal responsibility for health — is a fundamental principle of neoliberalism. David Harvey writes on this in the context of neoliberalism and labor: (emphasis added in this and subsequent quotations from Harvey)

[L]abour control and maintenance of a high rate of labour exploitation have been central to neoliberalization all along. The restoration or formation of [elite] class power occurs, as always, at the expense of labour.

It is precisely in such a context of diminished personal resources derived from the job market that the neoliberal determination to transfer all responsibility for well-being back to the individual has doubly deleterious effects. As the state withdraws from welfare provision and diminishes its role in arenas such as health care, public education, and social services, which were once so fundamental to embedded liberalism, it leaves larger and larger segments of the population exposed to impoverishment. The social safety net is reduced to a bare minimum in favour of a system that emphasizes personal responsibility. Personal failure is generally attributed to personal failings, and the victim is all too often blamed.

Personal responsibility for health — fundamental to healthism (a frequent topic on this blog) — serves the interests of neoliberalism in a number of ways. It can be used to justify reduced spending on health care and social services by the state. This is desirable in itself, according to neoliberals, but it also increases consumer spending on health care, which in turn benefits the health care, pharmaceutical, and insurance industries.

Holding individuals responsible for their health provides a convenient distraction from the underlying social and environmental causes of disease. Corporations are not financially or morally responsible for their externalities, such as the known carcinogens in our water, food, and air. The state is not responsible for the social and economic inequities that produce increased morbidity and mortality for those on the tail of the social gradient.

Personal responsibility increases consumption of health-related products, services, and media. It’s what Andrew Szasz calls an “inverted quarantine.” Rather than address problems in the physical and social environment that threaten our health and safety, individuals attempt to barricade themselves against the most obvious threats. We “shop our way to safety” by purchasing bottled water, organic food, sunscreen, and homes in gated communities. Of course, this option is only available to those social classes with sufficient income.

The neoliberal turn

Opposition to graphic health warnings on cigarette packaging is an example of neoliberalism’s preference for the upward redistribution of wealth over the public’s well being. This (to me) is where neoliberalism differs from simple capitalism. Capitalism seeks to maximize profits, of course, and it has certainly done that at the expense of the public. But neoliberalism now does this with relentless, undisguised enthusiasm.

The management of the New York fiscal crisis [1975] pioneered the way for neoliberal practices both domestically under Reagan and internationally through the IMF in the 1980s. It established the principle that in the event of a conflict between the integrity of financial institutions and bondholders’ returns, on the one hand, and the well-being of the citizens on the other, the former was to be privileged. It emphasized that the role of government was to create a good business climate rather than look to the needs and well-being of the population at large.

The legal system as a tool of neoliberalism

One way in which a society creates a climate favorable to business and financial interests is through its legal system.

Neoliberalism is in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade. The role of the state is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practices. The state … must … set up those military, defence, police, and legal structures and functions required to secure private property rights and to guarantee, by force if need be, the proper functioning of markets. …

A strong preference exists for government by executive order and by judicial decision rather than democratic and parliamentary decision-making.

The legal system has indeed become an instrument for the implementation of neoliberal policies. In the past, the constitution was interpreted in such a way that the government was allowed to regulate tobacco and pharmaceutical advertising. It was understood that the state had an interest in protecting the public’s health.

With the success of neoliberalism, this is no longer true. “Commercial” speech is now protected by the First Amendment. Corporations are as free to advertise and market their goods as individuals are to speak their minds.

As David Orentlicher writes: “The Supreme Court’s increasing sympathy for corporate speech and decreasing deference to public health authorities makes it more difficult for government to protect the public’s health.”

This is the political and economic world in which we now live.

Continued in part two.

Related posts:

What is healthism? (part one)

Healthy lifestyles serve political interests

The politics behind personal responsibility for health

Water privatization: An investment bonanza

Merchants of Doubt

Image source: Randommization

References:

David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism

Andrew Szasz, Shopping Our Way to Safety: How We Changed from Protecting the Environment to Protecting Ourselves

David Orentlicher, The FDA’s Graphic Tobacco Warnings and the First Amendment, The New England Journal of Medicine, July 18, 2013, Vol 369 No 3, pp 204-206

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.