The occasion for the rambling reflections on neoliberalism in the previous post was three “perspective” articles on tobacco in a recent issue of The New England Journal of Medicine. Two of them concern the FDA’s attempt to place graphic warnings on cigarette packs. The other is on cigarette smoking among the homeless.

The First Amendment

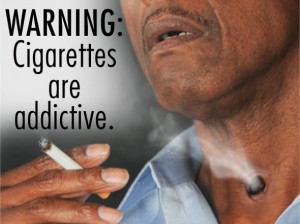

Placing graphic warnings on cigarette packs was part of the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. The tobacco industry sued the FDA (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA), claiming the warnings violated the industry’s First Amendment rights. In a case decided last year, the tobacco industry won.

Placing graphic warnings on cigarette packs was part of the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. The tobacco industry sued the FDA (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA), claiming the warnings violated the industry’s First Amendment rights. In a case decided last year, the tobacco industry won.

David Orentlicher, in his article The FDA’s Graphic Tobacco Warnings and the First Amendment, writes that the decision is both surprising and not surprising. It’s not surprising “given the Supreme Court’s increased sympathy toward corporations and their First Amendment rights. Regulations of commercial speech often succumb to judicial scrutiny.” It’s surprising because, while the Supreme Court now restricts the government’s power to regulate corporate speech, it has not in the past interfered with the government’s authority when it comes to regulating matters of public health. Evidently, that’s not the case anymore.

The upshot: (emphasis added)

[C]ompanies today are better able to promote their products, and government is less able to promote health than was the case in the past. Ironically, early protection of commercial speech rested in large part on the need to serve consumers’ welfare. In 1976, for example, the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia law that prevented pharmacists from advertising their prices for prescription drugs. The law especially hurt persons of limited means, who were not able to shop around and therefore might not be able to afford their medicines. Today, by contrast, courts are using the First Amendment to the detriment of consumers’ welfare, by invalidating laws that would protect the public health.

Graphics must not evoke an emotional response

The ruling against graphic warnings happened last August. In March of this year, the Justice Department announced it would not appeal the ruling to the Supreme Court. The second NEJM article, The FDA and Graphic Cigarette-Pack Warnings — Thwarted by the Courts, discusses the “remarkably restrained” response to this decision by advocates of tobacco control, including the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, the American Lung Association, and the American Public Health Association. This is in sharp contrast to protests last August that denounced the court’s ruling.

What’s going on here? It appears the administration was intimidated by the prospect of the Supreme Court making matters worse than they already are. “Some feared that the Court would use the opportunity of an appeal to reach beyond the graphic warnings the FDA had proposed — or to articulate even more exacting standards for reviewing commercial speech cases, hobbling future public health initiatives.”

So it’s back to the graphic drawing boards for the FDA. The courts may have set an impossible task. Graphic warnings are only allowed to convey the risks of smoking. They’re not allowed to promote anti-smoking. The FDA must provide evidence that the warnings are effective, but the graphics must be effective without producing an emotion.

“[C]ourt-acceptable” images that are also effective may be impossible to create. The appeals court rejected the use of cartoons that evoke emotion, while demanding proof of behavioral effects that may depend on the evocation of powerful feelings.

Even the hotline number included in the warnings — 1-800-QUIT-NOW — was objectionable. In her majority opinion against the warnings, US Circuit Judge Janice Rogers Brown wrote that it was “provocatively named.”

It will be at least two to three years before graphic warnings appear on cigarette packs in the US, if this happens at all. Meanwhile, forty countries, including Canada, Australia, France and the United Kingdom, require such packaging.

This costly setback for public health may well be measured in morbidity and mortality. … Increasingly, the United States stands alone, because of a constitutional doctrine privileging commercial speech above public health.

Let them eat cake

The third and final NEJM article on tobacco is on smoking among the homeless: Tobacco Use among Homeless People — Addressing the Neglected Addiction. Three quarters of homeless adults are cigarette smokers, four times the rate for adults in general and 2.5 times the rate for impoverished Americans in general.

Reducing the use of tobacco among the homeless is a difficult challenge for health care professionals. In the past, many have taken a fatalistic attitude towards the situation. The authors of this article make a strong case for reversing that attitude, while providing a realistic assessment of the obstacles.

I was surprised to learn (how naïve of me) that tobacco companies provide cigarettes to the homeless.

The tobacco industry has cultivated and capitalized on the culture of smoking among homeless people. In 1995, R.J. Reynolds launched Project SCUM, a “Sub-Culture Urban Marketing” plan targeting vulnerable groups in the San Francisco area, including “street people” in the Tenderloin. Tobacco-industry documents also reveal these companies’ efforts at building a consumer base in the homeless community through the distribution of branded blankets to homeless people, volunteerism at homeless service sites, and the provision of cigarettes to homeless shelters.

Project “SCUM”? (No one gave that a second thought?!) Free cigarettes for the homeless? This may be the modern day equivalent of “let them eat cake.” At least cake wasn’t addictive.

Freedom’s just another word

One of the arguments that contributes to a fatalistic attitude towards reducing tobacco use among the homeless is that cigarette smoking is one the very few pleasures available to the homeless. (emphasis added)

The psychological stress of fulfilling survival needs, the physical hazards of daily living, and the attendant expectation of premature death diminish the perceived benefits of smoking cessation in this population. Indeed, homeless people may view smoking as one of the few life domains over which they have control. Tobacco use thus becomes an expression of autonomy in the face of desperation and a source of comfort in the midst of chaos.

Does the government have the right (or the obligation) to influence the health behavior of its citizens? I can understand the economic justification. If the US government is going to pay for health care (as in Medicaid, Medicare, and various Affordable Care Act provisions), it’s in the government’s interest to reduce the costs of that health care. As we are frequently reminded, the escalating cost of health care threatens to take funds away from other necessities, such as police and fire protection, education, and a safe and sound infrastructure. (Of course, neoliberals don’t want the government to provide health care in the first place, which makes the economic argument a moot point for them.)

I have enough of a libertarian streak in me that I try to remain open minded on this issue. I do find paternalistic nudges from the government objectionable. David Brooks recently wrote an editorial in which he claimed there was no need to worry about the slippery slope issue when it comes to nudging. I’m more inclined to agree with Colin Crouch:

To do something to people without their being aware is to take advantage of their lack of knowledge or information. It is incompatible with both democratic and market principles; but it is of the essence of modern corporate behavior…. [I]f various psychological tricks are used to persuade people to buy things, would it not be better to use them to persuade people to be good citizens or look after their own health? But once politicians get to work on such an idea, its sinister side emerges, as transparency about what government is doing diminishes.

There was a nice reply to David Brooks by Mark White, author of The Manipulation of Choice: Ethics and Libertarian Paternalism. Also relevant here are Paul Crawshaw’s writings on the use of social marketing techniques to influence health behaviors (see here, here and here, plus References below).

What I really find objectionable is how neoliberalism perverts and subverts the very idea of freedom and autonomy. Let me conclude with a final quotation from David Harvey on the meaning of freedom: (emphasis added)

In a complex society, he [Karl Polanyi] pointed out, the meaning of freedom becomes as contradictory and as fraught as its incitements to action are compelling. There are, he noted, two kinds of freedom, one good and the other bad. Among the latter he listed ‘the freedom to exploit one’s fellows, or the freedom to make inordinate gains without commensurable service to the community, the freedom to keep technological inventions from being used for public benefit, or the freedom to profit from public calamities secretly engineered for private advantage‘. …

Planning and control are being attacked as a denial of freedom. Free enterprise and private ownership are declared to be essentials of freedom. No society built on other foundations is said to deserve to be called free. The freedom that regulation creates is denounced as unfreedom; the justice, liberty and welfare it offers are decried as a camouflage of slavery.

The idea of freedom ‘thus degenerates into a mere advocacy of free enterprise‘, which means ‘the fullness of freedom for those whose income, leisure and security need no enhancing, and a mere pittance of liberty for the people, who may in vain attempt to make use of their democratic rights to gain shelter from the power of the owners of property’.

… [I]t makes it all too clear why those of wealth and power so avidly support certain conceptions of rights and freedoms while seeking to persuade us of their universality and goodness. … The freedom of the market … turns out to be nothing more than the convenient means to spread corporate monopoly power and Coca Cola everywhere without constraint.

Related posts:

Do gruesome graphics deter or promote smoking?

Whatever you say, Phillip Morris

Coughing Up Blood Money: The Altria Earnings Protection Act?

Coughing Up Blood Money: FDA regulation of tobacco

Image source: AnnArbor.com

References:

David Orentlicher, The FDA’s Graphic Tobacco Warnings and the First Amendment, The New England Journal of Medicine, July 18, 2013, Vol 369 No 3, pp 204-206

David Orentlicher, The Commercial Speech Doctrine in Health Regulation: The Clash between the Public Interest in a Robust First Amendment and the Public Interest in Effective Protection from Harm, American Journal of Law and Medicine, Vol. 37, pp. 299-314, 2011

Tom Schoenberg. Tobacco Companies Win Challenge to U.S. Cigarette Label Law, Businessweek, August 24, 2012

Ronald Bayer, David Johns, and James Colgrove, The FDA and Graphic Cigarette-Pack Warnings — Thwarted by the Courts, The New England Journal of Medicine, July 18, 2013, Vol 369 No 3, pp 206-208

Travis P. Baggett, Matthew L. Tobey, and Nancy A. Rigotti, Tobacco Use among Homeless People — Addressing the Neglected Addiction, The New England Journal of Medicine, July 18, 2013, Vol 369 No 3, pp 201-204

David Brooks, The Nudge Debate, The New York Times, August 8, 2013

Colin Crouch, The Strange Non-death of Neo-liberalism

Mark D. White, David Brooks on libertarian paternalism and “nudge”, Economics and Ethics, August 9. 2013

Mark D. White, The Manipulation of Choice: Ethics and Libertarian Paternalism

Paul Crawshaw, Institutionalising commercialism? The case of social marketing for health in the UK, in Philip Whitehead and Paul Crawshaw (eds), Organising Neoliberalism: Markets, Privatisation and Justice

Paul Crawshaw, Governing at a distance: social marketing and the (bio) politics of responsibility, Social Science and Medicine, July 2012, 75 (1), pp.200-207

Paul Crawshaw and Chris Newlove, Men’s understandings of social marketing and health: Neo-liberalism and health governance, International Journal of Men’s Health, July 2011, 10 (2), pp.136-152

David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.