What follows are items I found interesting in magazines I’ve recently read. Normally I would have tweeted these links, but since I was on vacation from Twitter (see My Twitter vacation), I decided to create a type of blog post called Reading Notes (see Blogging and my Twitter vacation).

The bulleted titles below link to the specific item. There’s more detail on the articles I mention under References. OA indicates open access. $ indicates a pay wall. Note that emphasis in quotations has been added by me.

HEALTH CARE INEQUALITY

- Health equity: Should society or the medical profession be responsible for reducing health inequities?

MEDICALIZATION

- Breast cancer: Overdiagnosis and the benefits and risks of mammograms

THE DOCTOR/PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

- The iPatient: Does the education of millennial medical students teach them to regard the electronic health record as more real than the patient herself?

Health Care Inequality

• Health equity

Differences have narrowed in the way US health care is delivered to various racial and ethnic groups. Actual health outcomes, however, remain worse for blacks than for whites. This is documented in two recent NEJM articles: Racial and Ethnic Disparities among Enrollees in Medicare Advantage Plans and Quality and Equity of Care in U.S. Hospitals.

Simply standardizing the care provided to all patients will not be enough to address this inequity, as Marshall H. Chin writes in an editorial that accompanies the two articles: How to Achieve Health Equity.

Clinicians must help patients manage their health while patients are outside the clinic and living in the community — which is most of the time. … Eliminating disparities requires truly patient-centered care — that is, individualized care by clinicians who appreciate that patients’ beliefs, behaviors, social and economic challenges, and environments influence their health outcomes. …

Change cannot occur if clinicians and administrators believe that their care is optimal and that disparities are society’s problem. …

Governmental and private payers have largely been silent with regard to creating incentives explicitly to reduce disparities.

What Dr. Chin champions here is a highly commendable cause. Realistically, however, doctors — especially primary care physicians — are already overextended. They have little time during an office visit to discern the “beliefs, behaviors, social and economic challenges, and environments” that influence the health of their patients. They have very little time even to think about these issues, let alone to change the living conditions of their patients.

I detect very little political will in our society to address the conditions that create health disparities. Chin argues that change will not occur if the medical profession regards disparities as society’s problem. But these disparities are society’s problem, just as the shooting of unarmed black men by police officers is society’s problem. Chin’s editorial is admirable, but it will take more than the earnest and well-intentioned efforts of the medical professional to address this issue.

Medicalization

• Breast cancer

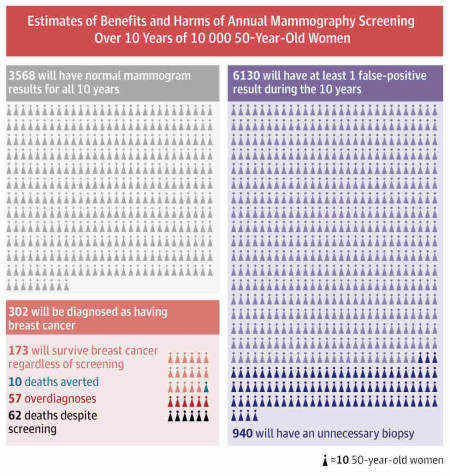

JAMA has a regular feature called the Patient Page at the end of most issues. A recent topic was the benefits and harms of annual mammography screening: Breast Cancer Screening: Benefits and Harms. It was accompanied by the above graphic, which nicely illustrates current findings.

The statistics in the graph are based on a recent review of risk and benefit studies. If 10,000 women, over a period of 10 years, started having annual mammograms at age 50, about 3,568 women would have normal exams, and 6,130 — more than half — would have at least one false positive. About 302 women would be diagnosed with cancer, and 10 lives would be saved thanks to screening.

What I find especially interesting here is how readily the message of overdiagnosis has been accepted by the medical profession. Not so long ago a discussion of the risks of mammograms would have featured the dangers of the radiation used to perform the test and just how carcinogenic that might be.

The question Can health screening damage your health? (an article by H. G. Stoate) has been around for decades. We’re greatly indebted, however, to H. Gilbert Welch for bringing this issue to the attention of both the medical profession and the public. He has focused not simply on the psychological consequences of false positives, as in the study by Stoate, but the medical consequences. In 2006 Gilbert published Should I Be Tested for Cancer?: Maybe Not and Here’s Why and in 2012 Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. His books were accompanied by editorials in medical journals and The New York Times.

The willingness to accept Gilbert’s message, rather than challenge it, may relate to the timing. The news was full of stories on how health care costs were rising so rapidly the US would soon be unable to fund education. In a fee-for service health care system, every diagnostic test increases costs. It’s difficult to restrain costs when profit motivates health care, but occasionally an appeal to restraint allows a worthy argument to prevail.

The Doctor/Patient Relationship

• The iPatient

In a 2008 article in NEJM, Abraham Verghese contrasted the “iPatient” (knowing the patient expediently through her test results and electronically recorded history) with the more traditional approach in which “the body is text.” In a recent issue of JAMA, Verghese and Jeffrey Chi make the case that the “flipped classroom” teaching model prepares doctors to prioritize the iPatient: Clinical Education and the Electronic Health Record: The Flipped Patient. In the flipped classroom, students prefer to watch lectures on video, rather than in the presence of the professor, who now speaks in a lecture hall “only half full.”

[S]tudents are just beginning to realize that technology meant to improve physician efficiency and patient outcomes can also unintentionally relegate their role to that of an observer or at best a passive participant. For a generation for whom texting can be more intimate than face-to-face conversation, there might be an assumption that the EHR [electronic health record] is the dialogue with the patient, not a representation of one. …

Students quickly realize that their clinical performance indirectly draws on their skills to use the EHR and represent it cogently in discussions with their patients, residents, and supervisors. Knowing the EHR is in a sense more important than knowing the real patient; mastering the former can often pass for familiarity with the actual patient. …

While it is important that students gain familiarity with the EHR during their training, this new technology must be accompanied by close observation and guidance. Given student preferences for flipped models of information acquisition and their desire to emulate house staff behavior, this will prove to be a great challenge. Millennial students are especially adept at leveraging technology to increase efficiency. Ultimately, however, the nature of medicine is the interaction of a vulnerable human being in distress with a caring empathetic team represented by other humans. It is vital to set EHR guidelines during training to foster skill in getting to know and care for patients.

This might make an interesting research project for someone who does digital sociology, assuming one could find enough medical students who do not already use electronic health records.

Related posts:

For U.S. health care, some are more equal than others

Two children visit their doctors: Social class in the USA

For-profit medicine and why the rich don’t have to care about the rest of us

Health inequities: An inhumane history

How we came not to care: Historical trends

From healthism to overdiagnosis

Medical screening, overdiagnosis, and the motives of for-profit hospitals

Screening for cancer and overdiagnosis

The downside of overly aggressive cancer screening

Creating an epidemic of cancer among the healthy

Electronic medical records, for-profit medicine, and the doctor-patient relationship

The doctor/patient relationship: What have we lost?

Pascal Bruckner on doctors and patients

My Twitter vacation

Blogging and my Twitter vacation

Image source: NPR

References:

John Z. Ayanian, Bruce E. Landon, Joseph P. Newhouse, and Alan M. Zaslavsky, Racial and Ethnic Disparities among Enrollees in Medicare Advantage Plans, NEJM, December 11, 2014, Vol 371, No 24, pp 2288-2297 ($)

Amal N. Trivedi, Wato Nsa, Leslie R.M. Hausmann, Jonathan S. Lee, Allen Ma, Dale W. Bratzler, Maria K. Mor, Kristie Baus, Fiona Larbi, and Michael J. Fine, Quality and Equity of Care in U.S. Hospitals, NEJM, December 11, 2014, Vol 371, No 24, pp 2998-2308 ($)

Marshall H. Chin, How to Achieve Health Equity, NEJM, December 11, 2014, Vol 371, No 24, pp 2331-2332 (OA)

Jill Jin, Breast Cancer Screening: Benefits and Harms, JAMA, December 17, 2014, Vol 312, No 23, p 2585 (OA)

Jeffrey Chi and Abraham Verghese, Clinical Education and the Electronic Health Record: The Flipped Patient, JAMA, December 10, 2014, Vol 312, No 22, p 2331 ($)

H G Stoate, Can health screening damage your health?, The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, May 1989, Vol 39, No 322, pp 193-195 ($)

Abraham Verghese, Culture Shock — Patient as Icon, Icon as Patient NEJM, December 25, 2008, Vol 359, No 26, pp 2748-2751 (OA) (link is to a PDF on Dr. Verghese’s website)

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.