Drugs are expensive and drive up the cost of health care. The problem with drug companies, however, is not simply that individual drugs are expensive. There’s a story in the news today about how the Obama victory and a Democratic congress may put downward pressure on drug prices. One industry analyst thinks this won’t be a serious problem since drugs have a very high markup: the number of products sold, not their price, drives industry growth. If health coverage expands, drug sales will increase, which is good news for drug companies.

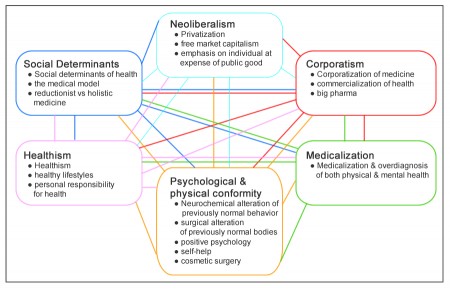

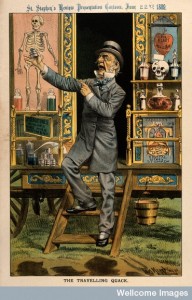

In 1976, the chief executive of Merck told Fortune magazine that he dreamed of marketing drugs the way Wrigley’s markets chewing gum: to as large a market as possible. The real problem with drug companies is their attempt to convince as many people as possible that they need drugs. This is disease mongering: expanding markets by convincing healthy people that they’re sick. Health has come to mean that feeling fine is an illusion easily shattered by the next news cycle or by the next prescription drug you’re encouraged to “ask your doctor about.”

When a patient has a disease and a doctor prescribes treatment, the doctor can observe whether or not the patient responds to the treatment. If the treatment doesn’t work, it’s discontinued. When a healthy patient is at risk for disease and a doctor prescribes treatment, there’s no way to be certain the treatment is working. The patient might never have gotten sick. So the treatment continues indefinitely. This wouldn’t be a problem if pharmaceuticals were harmless, but all drugs have side effects. The more people you treat with preventive pharmaceuticals, the more people there will be who suffer the adverse effects of treatment.

From Iona Heath: “[D]isease mongering exploits the deepest atavistic fears of suffering and death. … Human societies are riven by the effects of greed and fear. The rise of preventive health technologies has opened up a new arena of human greed, which responds to an enduring fear. The greed is for ever-greater longevity; the fear is that of dying. The irony and the tragedy is that the greed inflates the fear and poisons the present in the name of a better, or at least a longer, future. Ultimately, the only way of combating disease mongering is to value the manner of our living above the timing of our dying.”