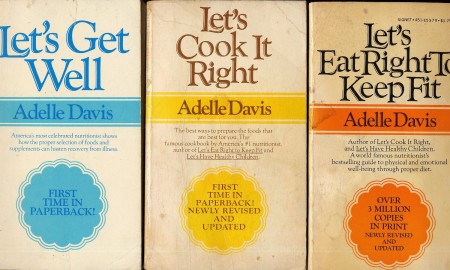

Let me begin by quoting a paragraph from Gyorgy Scrinis, a lecturer in food and nutrition politics and policy at the University of Melbourne. This is from a chapter called ‘Nutritionism and Functional Foods,’ which he contributed to the book The Philosophy of Food. Scrinis went on to publish an entire book on this subject, Nutritionism: The science & politics of dietary advice.

Just prior to the following paragraph, Scrinis has been discussing the dietary advice, from the 1960s to the 1990s, that it was better to eat margarine than butter. (Added emphasis in this and the following quotations is mine.)

The “mistake” of inadvertently promoting transfat-laden margarine is one of several mistakes, revisions, and backflips in scientific knowledge and dietary advice over the past century. Other cases include advice regarding dietary cholesterol, eggs, low-fat diets, and vitamin B. Yet these revisions do not seem to have tempered the sustained and confident discourse of precision and control that continues to pervade nutrition science, nor the willingness to translate limited and partial scientific insights into definitive population-wide dietary advice. I refer to this nutritional hubris as the myth of nutritional precision, as it involves an exaggerated representation of scientists’ understanding of the relationship between nutrients, foods, and the body and a failure to acknowledge the limits of the nutrient-level perspective. At the same time, the disagreements and uncertainties that exist within the scientific community with respect to particular nutritional theories tend to be concealed from, or misrepresented to, the lay public.