A few quotations on attitudes towards the pursuit health:

A few quotations on attitudes towards the pursuit health:

And do you not hold it disgraceful to require medical aid, unless it be for a wound, or an attack of illness incidental to the time of year, — to require it, I mean, owing to our laziness, and the life we lead, and to get ourselves so stuffed with humours and wind, like quagmires, so to compel the clever sons of Asclepius to call disease by such names as flatulence and catarrh.

– Plato, The Republic , 380 BC

, 380 BC

Yes, we suffer pain, we become ill, we die. But we also hope, laugh, celebrate; we know the joy of caring for one another; often we are healed and we recover by many means. We do not have to pursue the flattening out of human experience. I invite all to shift their gaze, their thoughts, from worrying about health care to cultivating the art of living.

– Ivan Illich, Health as One’s Own Responsibility – No, Thank You!, (PDF) 1990

After I had berated the patient for his obvious failure to comply with my recommendations to correct his “misbehavior,” he said, “You know, doctor, there is more to life than good health.” These words have helped me rein in my sometimes overzealous attempts to force patients into that glorious state of wellness and maintain a more realistic approach to the best possible state of health.

– Lewis E. Foxhall, M.D., The Tyranny of Health, 1994

Thinking that we can make death, illness, or privation easier to bear by preparing for them day and night is a sure way to poison our lives, to spoil the slightest pleasure by imagining its end.

– Pascal Bruckner, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy , 2000

, 2000

In the past, health was usually understood as the normal state of affairs, and taken for granted as [a] feature of life largely beyond the control of the person or the society. The proliferation of reflexive techniques which promise actually to improve one’s health has transformed the very meaning of the term ‘health’. The advent of such an immense range of popular ‘health-enhancement’ or ‘self-improvement’ techniques has meant that health is now seen more as a positive goal to be achieved rather than the normal state of a person without illness.

– Christopher Ziguras, Self-care: Embodiment, Personal Autonomy and the Shaping of Health Consciousness , 2004 (emphasis in the original)

, 2004 (emphasis in the original)

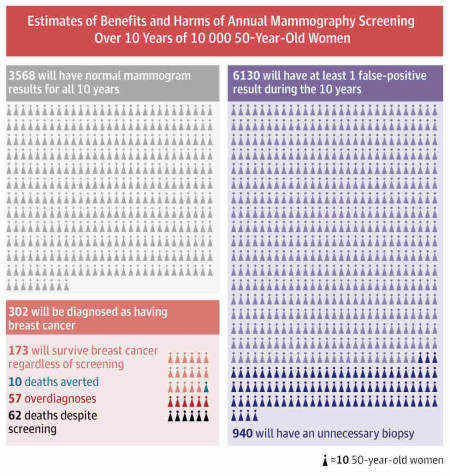

There have always been individuals willing to point out that the constant pursuit of health is not the be-all-and-end-all of life. This eminently reasonable attitude, however, is increasingly rare among both doctors and patients. We have been educated to believe – primarily by what Ziguras calls “commodified and mediated health advice,” but also by the medical and public health professions – that feeling good and assuming we’re healthy could all too easily be a delusion. How can we be certain some fatal disease doesn’t lurk in the unreliable interior of the body?

We choose to pursue health or to pursue disease

Read more