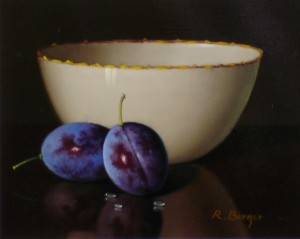

I have eaten

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

— William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams is part of an honorable tradition in the history of medicine — the physician/poet. He followed the example set by previous physician/poets, such as John Keats, Friedrich Schiller, and Oliver Wendell Holmes (of “Chambered Nautilus” fame). Physicians have also been writers, painters, musicians, philosophers, and – since the 19th century – photographers.

Yet in 1980 the historian G.S. Rousseau expressed concern that modern physicians no longer embodied the humanist tradition of their predecessors. Now that medicine had overwhelmingly become a science and not an art, he claimed, the interests and accomplishments of physicians had narrowed. (emphasis added)

In our century nothing has influenced the physician’s profile more profoundly than the loss of his or her identity as the last of the humanists. Until recently, physicians in Western European countries received broad, liberal educations, read languages and literature, studied the arts, were good musicians and amateur painters; by virtue of their financial privilege and class prominence they interacted with statesmen and high-ranking professionals, and continued in these activities through their careers. It was not uncommon, for Victorian and Edwardian doctors, for example, to write prolifically throughout their careers: medical memoirs and auto-biographies, biographies of other doctors, social analyses of their own times, imaginative literature of all types.

In twentieth-century America, the pattern has changed; only the most imaginative physicians can hope for this artistic lifestyle as a consequence of the economic constraints and housekeeping demands placed upon the doctor …. [T]he diminution of ‘humanist’ content in the training of physicians has lent an impression – perhaps falsely so but nevertheless pervasively – that medics are technicians, anything but humanists. As a by-product, it has nurtured a myth (already old by the eighteenth-century Enlightenment) that medicine is predominantly a science rather than an art. Both notions require adjustment if physicians hope to return to their earlier enriched, and probably healthier, role.

Rousseau’s comment on constraints (for “housekeeping demands” substitute “dealing with insurance”) is even more true today, especially for primary care physicians. A liberal education that values the humanist tradition is also in danger. See, for example, Martha Nussbaum’s Not For Profit , where she writes that contemporary education favors profitable, market-driven, career-oriented skills and devalues imagination, creativity, and critical thinking – qualities essential to the art and science of medicine.

, where she writes that contemporary education favors profitable, market-driven, career-oriented skills and devalues imagination, creativity, and critical thinking – qualities essential to the art and science of medicine.

But Rousseau’s assessment that physicians lack artistic interests is simply not true. Physicians continue to be prolific in their contributions to the ‘humanist’ tradition, most visibly as writers.

A plethora of physician/writers

Read more

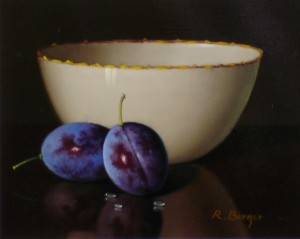

This entire poem is available online, so I hope JAMA won’t mind if I reproduce it here. The concept might seem simply clever at first, but in fact it’s quite thought provoking.

This entire poem is available online, so I hope JAMA won’t mind if I reproduce it here. The concept might seem simply clever at first, but in fact it’s quite thought provoking.