Back in May, Evgeny Morozov wrote a review for The New York Times Book Review of two books: The Naked Future: What Happens in a World That Anticipates Your Every Move? by Patrick Tucker and Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread — The Lessons From a New Science by Alex Pentland. The review is excellent. I’m mostly going to quote from this review (plus one of Morozov’s books), since this is a huge topic in which I have considerable interest but no expertise. I’ve been thinking about a JAMA article I read recently that discusses the need to convince the public to allow extensive use of Big Data in connection with health care (What’s that you bought at the grocery store? You didn’t renew your gym membership?), and Morozov’s ideas seem related. (Morozov, by the way, considers Big Data an “ugly, jargony name.”) Read more

Tag Archives: politics

For-profit medicine and why the rich don’t have to care about the rest of us

Jill Lepore has an article in a recent New Yorker called The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong. Her target is Clayton M. Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma and, specifically, disruptive innovation. As usual with Lepore, her essay is personable and well-argued. What I liked most about it, though, was its brief discussion of how unfortunate it is that professions such as higher education and medicine are being privatized (if they’re not already) and administered to maximize efficiency, making profits more important than students or patients. (emphasis added) Read more

Jill Lepore has an article in a recent New Yorker called The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong. Her target is Clayton M. Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma and, specifically, disruptive innovation. As usual with Lepore, her essay is personable and well-argued. What I liked most about it, though, was its brief discussion of how unfortunate it is that professions such as higher education and medicine are being privatized (if they’re not already) and administered to maximize efficiency, making profits more important than students or patients. (emphasis added) Read more

Healthy lifestyles: Social class. A precarious optimism

Continued from the previous post, where I noted that the Lalonde report — despite its good intentions — was followed by an emphasis on healthy lifestyles and personal responsibility for health, as well as increased health care costs.

Continued from the previous post, where I noted that the Lalonde report — despite its good intentions — was followed by an emphasis on healthy lifestyles and personal responsibility for health, as well as increased health care costs.

Personal responsibility and social class

In Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not?, Marmor et al, writing in 1994, were disappointed that the Lalonde report had not effectively prompted governments to address the underlying causes of health and disease. One reason for this, they believed, was that health policy reflects public opinion. If the public holds traditional views on what makes us sick (pathogens), what prevents disease (medical care), and what we can do to be healthy (take personal responsibility), new policies that include social determinants are unlikely. Those who are on the forefront of professional, scientific opinion may very well understand the importance of social determinants, but public opinion changes slowly. Without an education program, such as the relatively successful anti-smoking campaign, the public is unlikely to endorse change.

This is certainly true, although I believe there’s also something more fundamental at work here, namely, how a society accounts for the different life outcomes of its citizens. In Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Annette Lareau describes the assumptions people make when they hold others personally responsible for their life circumstances. Read more

Healthy lifestyles: The unfortunate consequences

Continued from the previous post, where I discussed the expansion of universal health care prior to the 1970s, how this created a growing demand for health care, and the problem health care costs posed for governments, especially when the economy suffered a downturn in the seventies. One response to the situation was to consider new ideas. Rather than limit strategies to what could be done by the health care industry, why not directly address the underlying causes of disease by considering social determinants of health.

Continued from the previous post, where I discussed the expansion of universal health care prior to the 1970s, how this created a growing demand for health care, and the problem health care costs posed for governments, especially when the economy suffered a downturn in the seventies. One response to the situation was to consider new ideas. Rather than limit strategies to what could be done by the health care industry, why not directly address the underlying causes of disease by considering social determinants of health.

Canada’s Lalonde report

In 1974, Canada produced the Lalonde report. It has been described as

[the] first modern government document in the Western world to acknowledge that our emphasis upon a biomedical health care system is wrong, and that we need to look beyond the traditional health care (sick care) system if we wish to improve the health of the public.

The US Congress emulated this thinking in 1976 by creating the Office of Prevention and Health Promotion. The US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare began publishing the document Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in 1979. The response in European countries — caught in the same bind of greater demand, increasing costs, and the financial consequences of a deteriorating economic landscape – was similar.

The common thread in these new perspectives on health was the assertion that health could be improved — without increasing health care costs — if we concentrated on such things as the work environment (occupational health), the physical environment (air and water pollution, pesticides and other carcinogens in food), genetics, and healthy lifestyles. The approach was broad: the environment was considered at least as important as the promotion of healthy lifestyles. Read more

Healthy lifestyles: The antecedents

In the 1970s, public health policies began to promote the idea that individuals are responsible for their health and therefore have an obligation to adopt healthy lifestyles. Over the ensuing decades, health became both an extremely popular topic for media coverage and a lucrative market for vendors of health-related products and services. What followed was a substantial increase in health consciousness and greater anxiety about all things that concern the body.

In the 1970s, public health policies began to promote the idea that individuals are responsible for their health and therefore have an obligation to adopt healthy lifestyles. Over the ensuing decades, health became both an extremely popular topic for media coverage and a lucrative market for vendors of health-related products and services. What followed was a substantial increase in health consciousness and greater anxiety about all things that concern the body.

Do healthy lifestyles actually produce better health? That they should may seem like common sense, which is one reason it’s been so easy to promote the idea that they do. The question is difficult to answer with absolute certainty, however. For one thing, the behavior that counts towards a healthy lifestyle does not readily lend itself to the objective measurements required for reliable scientific evidence. Defining health is also tricky. Lifespan is often used to compare the ‘health’ of different nations, but this fails to capture the subjective sense of health that is meaningful to individuals. Perhaps most important, while in theory a healthy lifestyle might improve health, that does little good if – as is now obvious – it’s extremely difficult to maintain behaviors that require things like changing what we eat and how often we exercise.

A related question would be: Did the promotion of healthy lifestyles reduce health care costs? This too seems like a sensible assumption, and the assertion is quite popular, especially among politicians. Health care costs have increased to hand-wringing levels. Promoting healthy lifestyles costs governments next to nothing, while the cost of health care is all too easily quantified. Read more

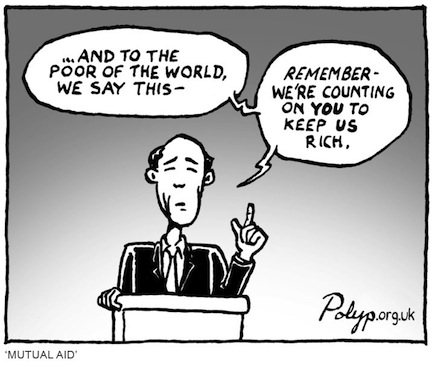

A more equitable future? US reveals its true intentions

Why is it so hard to convince policy makers worldwide to address the social determinants of health, including poverty, hunger, and income inequality? Judging by the excerpt below, we shouldn’t count on the US to champion this cause any time soon. It’s from a document called “The Future We Want,” issued by the Rio+20 conference last June. The US requested changes to the document, indicated in bold (additions) and strike-outs (deletions).

Why is it so hard to convince policy makers worldwide to address the social determinants of health, including poverty, hunger, and income inequality? Judging by the excerpt below, we shouldn’t count on the US to champion this cause any time soon. It’s from a document called “The Future We Want,” issued by the Rio+20 conference last June. The US requested changes to the document, indicated in bold (additions) and strike-outs (deletions).

Eradicating poverty is the greatest global challenge facing the world today and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development. In this regard we are committed to free humanity from extreme poverty and hunger as a matter of urgency.

We recognize that promoting

universalaccess to social services can make an important contribution to consolidating and achieving development gains.We strongly encourage initiatives

at all levelsaimed atprovidingenhancing social protection for all people. Read more

On healthism, the social determinants of health, conformity, & embracing the abnormal: (4) The abnormal part

Continued from parts one, two, and three.

Continued from parts one, two, and three.

A year ago, when I decided to call my declining rate of blogging a ‘sabbatical,’ I wrote down some questions to explore while I took time off to read.

How did we find our way into the dissatisfactions of the present – the commercialization of medicine, the corporatization of health care, the commodification of health? Does understanding the path we followed offer any insight into finding a better direction? Was the increasingly impersonal nature of the doctor-patient relationship inevitable once medicine became a science? Or was it only inevitable once health care emphasized profits over patients and the common good?

At the time I thought I would read primarily in the history of medicine, and that was how I started. Appreciating the historical context of medicine is important for understanding both how medicine ended up where it is today and what medicine could become. “The texture and context of the medical past provide perspective, allowing us to formulate questions about what we can realistically and ideally expect from medicine in our own time,” I wrote.

Now that I’ve become more familiar with the social determinants of health, I’m less optimistic about the future. The problem is not simply that the corporatization of health care has increased dissatisfaction among both doctors and patients. The problem is that our focus is so narrowly limited to health care systems that we fail to see the larger issue. As one metaphor puts it, doctors are so busy pulling diseased patients out of the river, there’s no time to look upstream and ask who’s throwing the bodies into the water. Read more

On healthism, the social determinants of health, conformity, & embracing the abnormal: (3) Connections

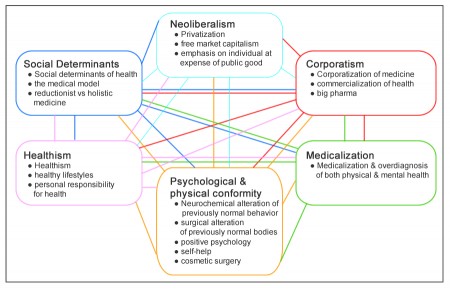

Continued from parts one and two, where I defined the terms used in the following diagram of my blogging interests. Click on the graphic for a larger image.

If I had written the previous two posts a year ago, I would have realized how much my interests were intertwined. I guess I wasn’t ready to do that. Anyway, in this post I catalog some of the connections.

Healthism

~ Healthism and psychological and physical conformity: Healthy lifestyle campaigns promote an ideal way of life that encourages individuals to alter their behavior and appearance. Although it’s true that we would all be better off if we didn’t smoke, that doesn’t make anti-smoking laws any less authoritarian, i.e., requiring conformity (see the section on anti-authority healthism in this post). The fitness aspect of healthy lifestyles promotes the desirability for both men and women of acquiring (i.e., conforming to) specific body images.

“Self-help is the psychiatric equivalent of healthism.” That’s a slogan I made up. I’m not sure yet if it will stand up to scrutiny. Certainly the self-help industry encourages self-criticism, which leads to a preoccupation with those aspects of personality currently considered undesirable. Read more

On healthism, the social determinants of health, conformity, & embracing the abnormal: (2) Economics & the socio-political

Continued from part one, where I discussed the first three of my six interests: healthism, medicalization, and psychological and physical conformity. Click on the graphic below to see a larger image.

The social determinants of health

Social determinants of health (often abbreviated SDOH) refers to unequally distributed social and economic conditions that correlate with unequal and inequitable distributions of health and disease. Presumably there is a causal relationship between the two, not merely a correlation. Definitively identifying the causal mechanisms, however, is difficult. A great many things influence our health (including things we’re not even aware of yet), and it can be difficult to isolate and scientifically study some of the ones we strongly suspect, like poverty, isolation, or a sense of being socially inferior.

The medical model is the preferred framework in modern westernized societies for explaining the distribution of health and disease. It emphasizes risk behavior (smoking, diet), clinical risk factors (blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol levels), genetics, health care access and quality, behavioral change, and patient education. One common characteristic of the medical model’s explanation of health and disease is that causes are located in the individual (behavior, genes), not in the individual’s economic and social environment. Read more

On healthism, the social determinants of health, conformity, & embracing the abnormal: (1) Bodies, minds & medicine

It’s always hard to be sure about these things, but I think the reason I decided to take a ‘sabbatical’ from blogging last July was that I was interested in too many seemingly unrelated topics. Writing about all of them left me feeling like I never got to the ‘meat’ of any one of them. And I couldn’t convince myself to focus on just one or two things, since that would mean abandoning the others, which I was unwilling to do.

Now that I’ve taken the past year to read and reflect, I find – duh! – that my interests are not as unrelated as I’d assumed. In hindsight, I should have realized this long ago, but, alas, I did not. I’m writing this post to clarify to myself what I now see as the common threads that connect my interests.

Here is a diagram that groups my interests into six categories. (Click on the graphic to see a larger image.)

Four of the six categories relate to all five of the others. The two outliers (neoliberalism and medicalization) are not as directly related as I feel the others are. Read more

Guest post: The unemployed as the waste products of the success factory

Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. We share an abiding interest in healthism or, as Pierre would say, santéisme. For the original version of this post, see L’individu devenu déchet. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. We share an abiding interest in healthism or, as Pierre would say, santéisme. For the original version of this post, see L’individu devenu déchet. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

Unlike some countries these days, America seems to have little difficulty tolerating the idea of multiculturalism. An explanation for this, perhaps, can be found in the American ideology of success. This ideology acts like a suction pump, removing any alternative explanations of how the world should work. This myth is contagious. The American dream – you can be whatever you want to be – circles the globe like a very powerful trademark.

In the myth of the self-made man, everything is possible. So powerful is this belief that nothing seems able to deter it. Contact with this idea creates the equivalent of an addiction. Every addiction, however, has its downside. We forget that every day “two types of trucks leave the factory: one type goes to the warehouse and department store, the other to the landfill. We have grown up with a story that considers only the first truck and ignores the second. ” [1] Read more

SCOTUS, the Affordable Care Act, and an ugly American tradition

I thought I had exhausted my need to read or listen to anything more on the Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). I read something today, however, that made me realize I hadn’t been paying close enough attention. It was an article published by The New England Journal of Medicine called The Road Ahead for the Affordable Care Act

I thought I had exhausted my need to read or listen to anything more on the Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). I read something today, however, that made me realize I hadn’t been paying close enough attention. It was an article published by The New England Journal of Medicine called The Road Ahead for the Affordable Care Act

The author, John McDonough, points out the significance of the upcoming November elections. In particular, he clarified for me why recent mentions of ‘reconciliation’ are not just referring to how the ACA was passed in 2010.

In January 2013, if Democrats hold the White House and Senate and regain control of the House, the ACA will be implemented mostly as constructed. If Republicans capture the White House and Senate and retain House control, the ACA will face major deconstruction early in 2013. Republican leaders will attempt to use Congress‘s budget-reconciliation authority to enact extensive repeal — and will need only 51 Senate votes, with no filibuster threat. If control of the White House and Congress is divided between the parties, then conflict over the law will persist. Thus, the November elections increasingly feel like a referendum on the ACA.

What is healthism? (part two)

In part one of this post I explained the most common meaning of healthism (an excessive preoccupation with healthy lifestyles and feeling personally responsible for our health) and described an authoritarian sense of the term. Here I discuss healthism as an appeal to moral sentiments and as a source of anxiety. I also note an unusual definition of the term as the desire to be healthy, which leads me to end with a personal disclaimer.

In part one of this post I explained the most common meaning of healthism (an excessive preoccupation with healthy lifestyles and feeling personally responsible for our health) and described an authoritarian sense of the term. Here I discuss healthism as an appeal to moral sentiments and as a source of anxiety. I also note an unusual definition of the term as the desire to be healthy, which leads me to end with a personal disclaimer.

Moral healthism

The directive to be personally responsible for our health – whether it comes from a government health policy, the medical profession, or an advertisement – is often fraught with unacknowledged moral overtones. People who practice healthy lifestyles (daily exercise, a Mediterranean diet) and dutifully follow prevention guidelines (annual cancer screenings, pharmaceuticals to maintain surrogate endpoints for risk reduction) are overtly or implicitly encouraged to feel morally superior to those who do not. This includes the right to feel superior to those who ‘choose’ to be unhealthy – after all, isn’t smoking a morally indefensible choice? The implication is that those who fail to take responsibility for their health are undeserving of our sympathy or assistance (especially financial).

This quality of healthism – like the anti-authority healthism discussed in part one – is possibly more common in the US than elsewhere. It’s unfortunate but true that in the US there’s a tendency to blame the poor and disadvantaged for not being able to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. There is a decided unwillingness to acknowledge that differences in wealth and social class during childhood have lifelong effects on behavior and health. Read more

What is healthism? (part one)

Throughout history there’s been an understandable desire to find connections between our behavior and our health. Human beings have practiced health regimens involving diet, exercise and hygiene since antiquity. When medicine was based on the humoral theory of disease, for example, individuals were advised to purge the body in the spring and, in the summer, avoid foods or activities that caused heat. Bathing in ice water was recommended in the 19th century. Mark Twain quoted the advice: “the only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d druther not.”

Throughout history there’s been an understandable desire to find connections between our behavior and our health. Human beings have practiced health regimens involving diet, exercise and hygiene since antiquity. When medicine was based on the humoral theory of disease, for example, individuals were advised to purge the body in the spring and, in the summer, avoid foods or activities that caused heat. Bathing in ice water was recommended in the 19th century. Mark Twain quoted the advice: “the only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d druther not.”

In the second half of the 20th century many Americans adopted the idea that a ‘healthy lifestyle’ (diet, exercise, not smoking, etc.) was a good way to prevent disease and live longer. This particular attitude was a product of popular perceptions about health (a surge of interest in holistic/alternative practices, self-care movements such as Our Bodies, Ourselves) and prevailing social attitudes (such as desirable body images). Perhaps more so than in previous centuries, the growth of media consumption and the effectiveness of modern advertising allowed commercial interests (books, magazines, fitness merchandise, vitamins and supplements, weight loss pills, diet and energy foods, …) to exert considerable influence on health behavior.

Also at work was extensive media coverage of a presumed link between preventive lifestyles and risk factors for disease (conflicting opinions about salt and which type of fats to eat are good examples). Unlike the vague aphorisms of previous generations, this more modern source of health advice had the scientific backing of epidemiology, if not the proof that comes from randomly controlled trials.

One of the terms used to describe the enormous increase in health consciousness is ‘healthism.’ Judging from how I’ve seen the word used, it means different things in different contexts to different people. I’m going to describe a few of those meanings.

This post grew rather long, so I’ve divided it into two parts. In part one I discuss an anti-authority sense of healthism as well as healthism’s most common meaning: a sense of personal responsibility for health accompanied by an excessive preoccupation with fitness, appearance, and the fear of disease. Part two discusses the moralistic and anxiety-inducing qualities of the term, plus an odd use where healthism becomes another word for health itself. Read more

Why medicine is not a science and health care is not health

Here’s something I read recently in a blog post (The Limits of (Neuro)science at Neuroskeptic) that started me thinking:

Here’s something I read recently in a blog post (The Limits of (Neuro)science at Neuroskeptic) that started me thinking:

Will science ever understand the brain? …

The notion that humans are complex and hard, while nature is easy, is an illusion created (ironically) by the successes of reductionist science. Some of the biggest questions facing mankind for eons have [been] answered so well, that we don’t even see them as questions. Why do people get sick? Bacteria and viruses. Why does the sun shine? Nuclear fusion. Easy.

I started to write a simple reply, but it grew into the following.

Medicine is an applied science, not a pure science

It may be true that understanding the human brain is only an order of magnitude more difficult than understanding any other aspect of human biology. I’m uneasy, however, about putting ‘why people get sick’ in the same category as ‘nuclear fusion.’ Particle physics is a science. Questions can be asked and (usually) answered under the controlled conditions required by the objectivity that characterizes science.

Medicine is the application of certain sciences (molecular biology, biochemistry, medical physics, histology, cytology, genetics, pharmacology, neuroscience) to – ultimately — individuals. Each individual is the product of a unique, lifelong sequence of social, cultural, economic, and psychological (as well as physical, chemical, biological, and genetic) influences. To this day, we don’t really know why some people get sick and others do not. To my mind, that makes medicine an application of science – like engineering – not a science in itself. Read more

Recommended (online) reading

I’m still on “sabbatical.” Mostly reading. Thinking about what I most want to write about. I know what my interests are — the problem is, I have too many. Meanwhile, here are some blogs I enjoy reading.

I’m still on “sabbatical.” Mostly reading. Thinking about what I most want to write about. I know what my interests are — the problem is, I have too many. Meanwhile, here are some blogs I enjoy reading.

Thought Broadcast by Dr. Steve Balt

Psychiatry is a controversial topic these days. We (speaking for myself, anyway) love to criticize the overprescription of psychopharmaceuticals, the medicalization of the slightest deviation from “normal,” and those psychiatrists who are eager to take “gifts” from the drug companies whose products they subsequently prescribe and promote.

I suspect people relate to psychiatry more readily than to the science of medicine. We’ve all known moments of slippage along the spectrum of mental health. We’d all like to understand ourselves better, something psychiatry used to promise before it tried to reduce us to the chemical interactions inside our brains.

Dr. Balt writes about all of this. What I especially like about his blog is his compassion for patients and his honest assessment of the psychiatric profession. His writing has a quality like Gawande’s: He maintains a strong personal presence without straying too far into the overtly personal.

To get a sense of Thought Broadcast, read Dr. Balt’s My Philosophy page. A recent post I’d recommend: How to Retire at Age 27. It’s on psychiatric qualification for disability. His point is that labeling (and medicating) someone as disabled does nothing to solve underlying social problems. It concludes:

Psychiatry should not be a tool for social justice. … Using psychiatric labels to help patients obtain taxpayers’ money, unless absolutely necessary and legitimate, is wasteful and dishonest. More importantly, it harms the very souls we have pledged an oath to protect.

When the poor were contagious

The Western world first industrialized in Great Britain, prompting vast numbers of inhabitants to move from the agricultural countryside to urban centers. Living and working conditions were deplorable. Andrew Mearn wrote in 1883 of the “pestilential human rookeries … where tens of thousands are crowded.” He continues:

The Western world first industrialized in Great Britain, prompting vast numbers of inhabitants to move from the agricultural countryside to urban centers. Living and working conditions were deplorable. Andrew Mearn wrote in 1883 of the “pestilential human rookeries … where tens of thousands are crowded.” He continues:

To get to them you have to penetrate courts reeking with poisonous and malodorous gases arising from accumulations of sewage and refuse scattered in all directions and often flowing beneath your feet; courts, many of them which the sun never penetrates, which are never visited by a breath of fresh air, and which rarely know the virtues of a drop of cleansing water…. You have to grope your way along dark and filthy passages swarming with vermin. Then, if you are not driven back by the intolerable stench, you may gain admittance to the dens in which these thousands of beings who belong, as much as you, to the race for whom Christ died, herd together.

Pretty graphic. Roy Porter’s comment on this passage: “Historians still dispute whether industrialization raised or depressed wages and living standards – something, perhaps, impossible to measure.” Read more

The misuse of health statistics by politicians

[This post contains links to the New York Times. If you position your mouse over a link, you can view the destination URL at the bottom of your browser.]

[This post contains links to the New York Times. If you position your mouse over a link, you can view the destination URL at the bottom of your browser.]

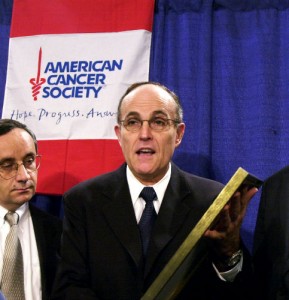

When former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani was seeking the Republican presidential nomination in 2007, he used to give a campaign speech that referred to prostate cancer and health care. His sound bites were turned into a radio commercial and included the following:

I had prostate cancer five, six years ago. My chance of surviving prostate cancer — and, thank God, I was cured of it — in the United States? Eighty-two percent. My chance of surviving prostate cancer in England? Only 44 percent under socialized medicine.

What’s wrong with this picture? Several things.

The numbers themselves – the 82 and 44 percent — were incorrect. Chances of survival are typically stated as the prospect of living another five years. According to the National Cancer Institute, the five-year survival rate for prostate cancer in the US is 98.4%. For England (according to the United Kingdom’s Office of National Statistics), the number is 74.4%.

Where did the lowly 44% for England come from? Giuliani’s health care adviser started with the number of people who have prostate cancer and the number who die (called incidence and mortality rates): how many people have the disease in a given year and how many die from the disease in that year. From those numbers he came up with a five-year survival rate. This is not possible. “Five-year survival rates cannot be calculated from incidence and mortality rates, as any good epidemiologist knows,” according to the Commonwealth Fund.

Comparing apples to oranges

Why is it so hard to reduce US health care costs?

Professor Victor Fuchs and Dr. Arnold Milstein, both of Stanford University, have an article in a recent issue of The New England Journal of Medicine that asks: Why is it so difficult to reduce health care costs in the US? The article is available in its entirety online, but for those short of time, here’s a concise (and depressing) summary.

Professor Victor Fuchs and Dr. Arnold Milstein, both of Stanford University, have an article in a recent issue of The New England Journal of Medicine that asks: Why is it so difficult to reduce health care costs in the US? The article is available in its entirety online, but for those short of time, here’s a concise (and depressing) summary.

The graphic accompanying the article is dramatic in its simplicity. Health care spending in the US is 17% of GDP. In other developed countries (Western Europe, Canada, Australia), the number fluctuates around 10%. And yet life expectancy in the US is the lowest of these countries – almost four years below that of the number one country.

We know that some physicians and health care providers manage to operate at less than 20% of the average cost of care, without sacrificing quality. If everyone followed their example, the US could save $640 billion a year (US health care costs for 2008 were $2.3 trillion). Why doesn’t that happen, or as Fuchs and Milstein put it: “Why don’t cost-effective models diffuse rapidly in health care, as they do in other industries?” The answer comes down to perceptions and behaviors. Read more

Bruckner on the good life, money, and the unequal world of work

Once more, from Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy

Once more, from Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy. This time on our relation to wealth.

Why is it American conservatives deplore European social democracy? Could it be that it doesn’t stimulate consumerism enough to satisfy a free market economy? (emphasis added in the following quotations)

[T]he power of the great upheavals of the preceding century in France, including those of 1936 and 1945, consisted not only in redistributing the social pie, but also in creating new kinds of opulence for the majority of the people: free time, poetry, love, the liberation of desire, the sense of everyday transfiguration. Not being content to manage penury, but discovering everywhere new goods that are unquantifiable and escape the rule of profit, prolonging the old revolutionary dream of luxury for everyone, of beauty made available to the most humble. Today, luxury resides in everything that is becoming rare: communion with nature, silence, meditation, slowness rediscovered, the pleasure of living out of step with others, studious idleness, the enjoyment of the major works of the mind – these are all privileges that cannot be bought because they are literally priceless. Then we can oppose to an involuntary poverty a voluntary poverty (or rather a voluntary self-restriction) that is in no way a choice to be indigent but rather a redefinition of our personal priorities. This may involve giving up things, preferring freedom to comfort, to an arbitrary social status, but for a larger life, for a return to the essential instead of accumulating money and objects like a ludicrous barrier set up against fear and death. In the end, true luxury is the invention of one’s own life, master over one’s destiny; “but everything that is precious is as difficult as it is rare” (Spinoza).

This is not to say that Bruckner fails to appreciate the situation of the poor. Written in 2000, way before the financial crisis, this comment is even more relevant today:

[P]overty in developed countries may never be overcome, simply because the rich no longer … need the poor to get rich. … The misfortune of being exploited has been succeeded by the still worse misfortune of no longer being exploitable.

Why are we so willing to undergo cosmetic surgery?

The high rate of cosmetic surgery in Asia has been widely discussed, including an article in The New York Times. What caught my attention in this more recent piece was the postmodern/feminist spin.

Susan Feiner, a feminist economist, offers these comments: (emphasis added)

Parents are caught between a traditional world view and a postmodernist world view. On the traditional side especially, your daughter is your property and potential to social advancement. … On the postmodern side you have this idea that western beauty, this imported beauty ideal, is really a sign of your family’s openness to the future. So those two impulses – a very traditional impulse and the more modern neo-liberalism impulse come together at the moment of submitting your own daughter to the knife. …

On one hand we have all of this acceptance and even approval for women to become doctors and lawyers and political leaders and at the same time what’s been held up to women is this Walt Disney notion of our lives. That really even if you are a doctor or a lawyer or a political leader the best you can really do is to be beautiful and get some wealthy rich man to take care of you, so the best possible outcome for any women is to be both hugely successful professionally and be knock-down beautiful.

Why so much willingness to reshape the body?

What drives the popularity of cosmetic surgery? As bioethicist Carl Elliott notes in one of my favorite books, Better Than Well, medical enhancements, along with body size, are part of the logic of consumer culture: “You cannot simply opt out of the system and expect nobody to notice how much you weigh.” Read more

Guest post: A sound mind in a disintegrating body

In an attempt to balance my very serious attitude towards the subject of healthism – the idea that individuals should be held personally responsible for their health; an idea promoted at a time of rising health care costs in the “Great Society” seventies, appealing to residual American sentiments of self-reliance and individualism, conveniently distracting attention from social and environmental determinants of health …

In an attempt to balance my very serious attitude towards the subject of healthism – the idea that individuals should be held personally responsible for their health; an idea promoted at a time of rising health care costs in the “Great Society” seventies, appealing to residual American sentiments of self-reliance and individualism, conveniently distracting attention from social and environmental determinants of health …

I could go on, but as I was saying, in an attempt to provide balance, I offer this guest post by Kate Gilderdale, a writer who valiantly resists healthism propaganda and whose approach to any subject is always liberally laced with humor. Kate blogs at The Jaundiced View (where this post first appeared), and I highly recommend a daily visit (laughter being the best medicine and all).

Mens sana in corpore sano is today’s mantra for many people, but a lot of us only manage to fulfil half the equation at best.

In order to attain the corpore sano required by today’s fanatical health and hotness community you have to devote two or three hours a day to honing the body beautiful so that it contains no lumps, bra overhang or bits that have to be sucked in when you walk past a mirror. This involves lunges, squats, curls, lat pulldowns, pushups, bench presses and eventual death from exhaustion unless you are of that rare elite who are truly in The Zone.

The rest of us get by by avoiding spandex and investing in Spanx, whilst using those three hours not spent at the gym to fill our brains with stuff that we hope will make us appear erudite without being unforgivably elitist.

When it comes to physical exertion, Joan Rivers said it best. “I don’t exercise. If God wanted me to bend over, he would have put diamonds on the floor.”

Any deviations from Americanized spelling (“fulfil”) may be attributed to Kate’s proper British education.

Joseph Stiglitz on inequality

Great essay by Joseph Stiglitz on income inequality: “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%” in Vanity Fair.

Great essay by Joseph Stiglitz on income inequality: “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%” in Vanity Fair.

As we gaze out at the popular fervor in the streets [of the Middle East/North Africa], one question to ask ourselves is this: When will it come to America? In important ways, our own country has become like one of these distant, troubled places.

Alexis de Tocqueville once described what he saw as a chief part of the peculiar genius of American society—something he called “self-interest properly understood.” The last two words were the key. Everyone possesses self-interest in a narrow sense: I want what’s good for me right now! Self-interest “properly understood” is different. It means appreciating that paying attention to everyone else’s self-interest—in other words, the common welfare—is in fact a precondition for one’s own ultimate well-being. Tocqueville was not suggesting that there was anything noble or idealistic about this outlook—in fact, he was suggesting the opposite. It was a mark of American pragmatism. Those canny Americans understood a basic fact: looking out for the other guy isn’t just good for the soul—it’s good for business.

The top 1 percent have the best houses, the best educations, the best doctors, and the best lifestyles, but there is one thing that money doesn’t seem to have bought: an understanding that their fate is bound up with how the other 99 percent live. Throughout history, this is something that the top 1 percent eventually do learn. Too late.

Down so low we dare not speak

Due to multiple, largely uncontrollable influences that include both nature and nurture, individual outlooks on the world are arrayed along a continuum from bright to dark. I tend to land on the dark side.

Due to multiple, largely uncontrollable influences that include both nature and nurture, individual outlooks on the world are arrayed along a continuum from bright to dark. I tend to land on the dark side.

Three weeks ago I read a darkish blog post that made a strong impression on me. I was especially struck by its characterization of the current political/economic climate as so depressing one hesitates to speak of it. I understand that sentiment.

I couldn’t remember where I read it and recently tried in vain to locate it in all my usual web haunts. Then last night it popped up like an old friend. It’s called “The New American Pessimism,” and it’s written by the Serbian-American poet Charles Simic, a Pulitzer Prize winner, among other things. Here’s an excerpt. (emphasis added)

It must be difficult for any hostess nowadays to stop her dinner guests from reciting to each other over the course of an evening the endless examples of lies and stupidities they’ve come across in the press and on TV. As they get more and more wound up, they try to outdo each other, losing all interest in the food on their plates. I know that when I get together with friends, we make a conscious effort to change the subject and talk about grandchildren, reminisce about the past and the movies we’ve seen, though we can’t manage it for very long. We end up disheartening and demoralizing each other and saying goodnight, embarrassed and annoyed with ourselves, as if being upset about what is being done to us is not a subject fit for polite society. …

By the president’s calculation, telling the truth to the American people would doom his reelection campaign, since he would not be able to raise the billion dollars he needs this time around. The kind of people who have that kind of money and will agree to contribute to his campaign know very well what informed voters in a working democracy would to do to them once they understood just who has depleted the national treasury to line their own pockets. No doubt, he and his political party will do anything to avoid the truth and will propose outwardly attractive solutions—like the health care bill that not only expands coverage but greatly benefits insurance companies and does little to reduce healthcare costs. They hope that these kinds of measures will lure the majority of voters who won’t bother to learn the details, but they will also send a clear signal to the moneyed classes that they won’t be inconvenienced in the least. … Read more

Breaking the self-destructive meritocratic spell

Intelligent, thoughtful essay by Namit Arora on distributive economic justice: libertarian, meritocratic, egalitarian. (emphasis added)

Intelligent, thoughtful essay by Namit Arora on distributive economic justice: libertarian, meritocratic, egalitarian. (emphasis added)

In Rawlsian terms, the problem in America is not that a minority has grown super rich, but that for decades now, it has done so to the detriment of the lower social classes. The big question is: why does the majority in a seemingly free society tolerate this, and even happily vote against its own economic interests? A plausible answer is that it is under a self-destructive meritocratic spell that sees social outcomes as moral desert—a spell at least as old as the American frontier but long since repurposed by the corporate control of public institutions and the media: news, film, TV, publishing, etc. Rather than move towards greater fairness and egalitarianism, it promotes a libertarian gospel of the free market with minimal regulation, taxation, and public safety nets. What would it take to break this spell?

What Wisconsin hath wrought

It’s time to focus on the corporate CEOs and speculators. … “In U.S. states facing a budget shortfall, revenues from corporate taxes have declined $2.5 billion in the last year. In Wisconsin, two-thirds of corporations pay no taxes, and the share of state revenue from corporate taxes has fallen by half since 1981.” The same is true in other states. These facts must be stressed, repeatedly and aggressively, if the debate is going to shift from cuts in public services and education to demands for fair taxes and the revenues necessary for services and schools. Read more

It’s time to focus on the corporate CEOs and speculators. … “In U.S. states facing a budget shortfall, revenues from corporate taxes have declined $2.5 billion in the last year. In Wisconsin, two-thirds of corporations pay no taxes, and the share of state revenue from corporate taxes has fallen by half since 1981.” The same is true in other states. These facts must be stressed, repeatedly and aggressively, if the debate is going to shift from cuts in public services and education to demands for fair taxes and the revenues necessary for services and schools. Read more

Daniel T. Rodgers on equality and inequality

Rawls’s cautious, prudential argument for equality could not be uncoupled in the minds of conservative intellectuals from their distress at the new affirmative action projects, their anger at busing for racial equalization, and their recoil from the gender-blurring prospects of the Equal Rights Amendment. The once common distinction between equality of opportunity and the (dangerous) passion for equality of results fused into a general criticism of equality-driven politics in all its forms. Freedom, merit, and excellence: these, not equality, were the aims of the good society. Michael Novak put the conservative consensus succinctly in 1990: “The rage for equality is a wicked project.” Read more

Rawls’s cautious, prudential argument for equality could not be uncoupled in the minds of conservative intellectuals from their distress at the new affirmative action projects, their anger at busing for racial equalization, and their recoil from the gender-blurring prospects of the Equal Rights Amendment. The once common distinction between equality of opportunity and the (dangerous) passion for equality of results fused into a general criticism of equality-driven politics in all its forms. Freedom, merit, and excellence: these, not equality, were the aims of the good society. Michael Novak put the conservative consensus succinctly in 1990: “The rage for equality is a wicked project.” Read more

Ezra Klein on inequality

Whatever our eventual conclusions on inequality, we’re going to have trouble acting on them if the political system can’t bring itself to care about the average American a little bit more. … We at least need to recognize what it is that we keep doing: green-lighting the policies that make the rich richer or, in the case of the crisis, keep them rich, while dithering and drifting on the problems and needs of the vast middle. Read more

Whatever our eventual conclusions on inequality, we’re going to have trouble acting on them if the political system can’t bring itself to care about the average American a little bit more. … We at least need to recognize what it is that we keep doing: green-lighting the policies that make the rich richer or, in the case of the crisis, keep them rich, while dithering and drifting on the problems and needs of the vast middle. Read more

Even dictators need a facelift

It’s not surprising then that Colonel Muammar Gaddafi of Libya would want to maintain a youthful appearance. His Brazilian plastic surgeon, Dr. Liacyr Ribeiro, has just released the details. Ribeiro – who has also performed cosmetic surgery on Italy’s Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi — told a Brazillian weekly that he operated on Gaddafi in 1995. Read more

It’s not surprising then that Colonel Muammar Gaddafi of Libya would want to maintain a youthful appearance. His Brazilian plastic surgeon, Dr. Liacyr Ribeiro, has just released the details. Ribeiro – who has also performed cosmetic surgery on Italy’s Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi — told a Brazillian weekly that he operated on Gaddafi in 1995. Read more

The complex signaling function of hair

In popular culture, to have white skin and gray hair is to be old (unemployable and unattractive) or menopausal (unproductive and unsexual). An attempt to retain their hair color (natural or chosen) is, for certain women, an attempt to retain a currency of employability, utility and desirability. Read more

In popular culture, to have white skin and gray hair is to be old (unemployable and unattractive) or menopausal (unproductive and unsexual). An attempt to retain their hair color (natural or chosen) is, for certain women, an attempt to retain a currency of employability, utility and desirability. Read more