A scant few hundred years ago we began to believe we could understand the world through reason and science. Not only that, we believed we could bring it under our control. These new beliefs brought many wonderful things: Electricity, modern medicine, iPods.

Risks have always been with us: natural disasters, wild animals, accidents, epidemics, and other ‘acts of god’. But over the last century, especially since World War II, new categories of risk emerged. These modern risks follow from the negative byproducts and side effects of the very same science, technology, industrialization, and global economy that we otherwise benefit from and enjoy.

Global warming, environmental carcinogens, toxic waste disposal – all these effects of technology reach forward in time to touch future generations. Such trans-generational risk is uniquely post-industrial. Some of these, like species extinction – which can now result from human activity – are irreversible.

But modern risk has not only expanded through time. Tainted products from anywhere in the world – food, toys, or jewelry for children – can end up on any local store or pantry shelf. These modern risks are not merely medical and ecological, but psychological as well: Is this can of tuna safe to eat?

As our dependence on technology and a global economy increases, the negative consequences are more difficult to predict, or to control when prediction fails. What are the implications of mapping and sequencing the human genome? Perhaps we’ll recreate a long-extinct species. Will these make nice pets or nice nightmares?

Before and after science

In the heady days of the Enlightenment we looked towards a Utopian future, the promise of science, technology, rationalism. Yet only in Frankensteinian fiction did we ever consider the down sides of this brave new world. It’s a bit like how the Bush administration failed to plan the post-invasion phase of the Iraq war. Compared to the impacts of industrialization, globalization, and mass media, that one should have been a no-brainer.

In the heady days of the Enlightenment we looked towards a Utopian future, the promise of science, technology, rationalism. Yet only in Frankensteinian fiction did we ever consider the down sides of this brave new world. It’s a bit like how the Bush administration failed to plan the post-invasion phase of the Iraq war. Compared to the impacts of industrialization, globalization, and mass media, that one should have been a no-brainer.

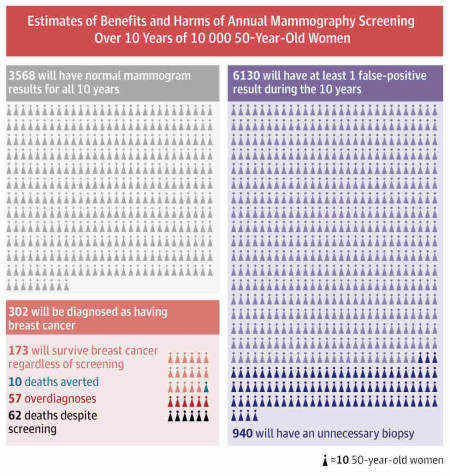

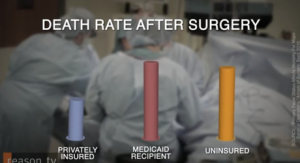

Today’s risks get defined by scientists, lawyers, and politicians, whose differing interests are often reflected in those definitions. “Yes, there’s mercury in your salmon and melamine in little Jenny’s formula, but not enough to do any real damage.”

Risks are communicated, breathlessly and repeatedly, by a media whose interests may not be identical with those of “viewers like you.” Perhaps a lack of confidence in our information sources is an even greater risk than lack of confidence in our food supply.

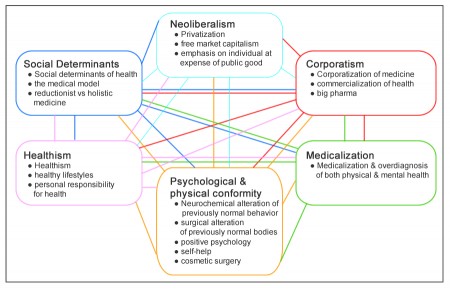

Humans could never control natural disasters. Now we are losing control of the man-made ones. But we try to control what we think we can. So we regularly lift weights and practice yoga, or at least try to. We buy organic food and avoid trans fats. We practice a ‘healthy lifestyle’ (or at least try to), even though behavior has less influence on overall health than genetics, social status, economic inequality, and environmental degradation. Those are all beyond the direct control of individuals. So we drink pomegranate juice instead, distracting ourselves from the complex and real issues at the root of our suspicions, outrage, and despair.

Related posts:

The earth’s scars

Negative knowledge: Remembering Alfred Schutz

Melamine, cadmium, and Heidi Montag

To make more money

Melamine update

Eat fish? Don’t read this