The policies of Margaret Thatcher have been characterized as dog-eat-dog social Darwinism. On matters of health she refused to use the word “inequalities,” preferring instead to speak of “variations” in health. One of those well-documented “variations”: people who lived in the poorest neighborhoods didn’t live as long as people who lived elsewhere.

The policies of Margaret Thatcher have been characterized as dog-eat-dog social Darwinism. On matters of health she refused to use the word “inequalities,” preferring instead to speak of “variations” in health. One of those well-documented “variations”: people who lived in the poorest neighborhoods didn’t live as long as people who lived elsewhere.

Thatcher was prime minister of the UK until 1990 and was succeeded by John Major, another Conservative Party member. But in 1997 political power shifted to the Labour Party, when Tony Blair became prime minister. In its political campaign, Labour had promised to address the problem of health inequalities.

“New Labour came in 1997 and announced it would put reducing health inequalities at the heart of tackling the root causes of ill-health,” reports The Guardian. Sure enough, once in office, the Labour government created a commission: The Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. Hopes were high that inequities would be addressed.

Where was the medical profession?

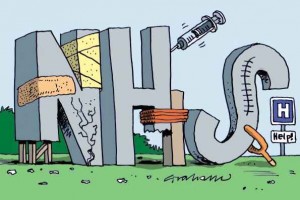

A recent report from Labour’s public accounts committee details what’s happened since 1997, and it’s not a pretty picture. The difference in life expectancy between the poorest areas and the national average increased 7% for men and 14% for women. The national average for the number of doctors per 1000 residents is 0.6. For poor areas of the country, that number is 0.25. (The number for the US is 1.6.)

The medical journal The Lancet describes the report as “a tale of decrepitude at every level of the health system.” The report’s author, Margaret Hodge, commenting on information she received from the Department of Health’s Permanent Secretary, described his “claptrap” as “despairing.” Virtually nothing has been done since 1997. “[T]hat is just gobsmacking,” said Hodge. According to another source, “it’s a mess, it’s a tragedy really.”

Part of the blame for inaction can be assigned to the government and the civil service. But in its editorial on the subject, The Lancet comes down particularly hard on the medical profession. (emphasis added)

Where was the medical profession? Doctors are supposed to feel an acute responsibility to deliver the best health service to the whole population. It is on this basis that they ask the public and government to support generous pay increases and terms and conditions of service. These attitudes and behaviours are what we commonly mean by professionalism. It seems that doctors failed completely to live up to the rhetoric of their commitment to professional values. Members of Hodge’s committee tried to find out why doctors had been so reluctant to address inequalities themselves. There are some simple and proven interventions that, if implemented evenly across the population, would go a long way to reduce inequalities in health—notably, smoking cessation and the treatment of high blood pressure and raised cholesterol. But doctors did not respond to the clear public and political call to take action on inequalities (and nor did the media). Instead, they sought to massively increase their salaries in a new general practitioner (GP) contract in 2005, one that itself was empty of commitment to reduce inequalities. People died because of this professional failure. The negotiators of that GP contract, together with the Department of Health, share a responsibility for those deaths.

Bureaucracy let the country down. Shamefully.

The UK Department of Health has over 2300 employees, and its Permanent Secretary is paid $274,000 a year. (For comparison, Sanjay Gupta was offered $153,000 to be Surgeon General.) The Department obviously failed to deliver on Labour’s election mandate, and The Lancet editorial does not spare them.

A bureaucracy’s first priority is usually to protect itself. Only secondarily will it try to deliver on the pledges of its political leaders. To call this period in the Department’s history shameful does not even begin to do justice to the way it let down the millions of people to whom it owed a duty to serve. Despite the bland reassurances made to the Public Accounts Committee, there is not one shred of evidence that the Department has learned the lessons of this agonising debacle.

What I find so refreshing about all this is that a major medical journal would speak out so strongly about health inequality. I wish we heard more of that passion here in the US.

Related posts:

Life expectancy of the rich and the poor

Health inequities, politics, and the public option

Déjà vu: Historical resistance to the inequities of health

Health inequities: An inhumane history

Resources:

Image source: Psychiatric Nurses – RMN

“Claptrap” from the UK’s Department of Health, The Lancet, November 13, 2010, Vol. 376 Issue 9753, p. 1617

Randeep Ramesh, MPs attack Labour inaction on health inequality, The Guardian, November 2, 2010

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by benmckendrick, Jan Henderson. Jan Henderson said: Professionalism of UK doctors questioned over health inequalities http://j.mp/ellwkh Doctors failed to live up to their professional values […]