Here’s something I read recently in a blog post (The Limits of (Neuro)science at Neuroskeptic) that started me thinking:

Here’s something I read recently in a blog post (The Limits of (Neuro)science at Neuroskeptic) that started me thinking:

Will science ever understand the brain? …

The notion that humans are complex and hard, while nature is easy, is an illusion created (ironically) by the successes of reductionist science. Some of the biggest questions facing mankind for eons have [been] answered so well, that we don’t even see them as questions. Why do people get sick? Bacteria and viruses. Why does the sun shine? Nuclear fusion. Easy.

I started to write a simple reply, but it grew into the following.

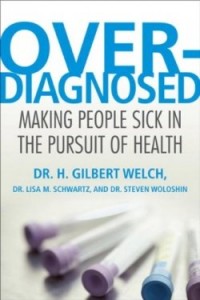

Medicine is an applied science, not a pure science

It may be true that understanding the human brain is only an order of magnitude more difficult than understanding any other aspect of human biology. I’m uneasy, however, about putting ‘why people get sick’ in the same category as ‘nuclear fusion.’ Particle physics is a science. Questions can be asked and (usually) answered under the controlled conditions required by the objectivity that characterizes science.

Medicine is the application of certain sciences (molecular biology, biochemistry, medical physics, histology, cytology, genetics, pharmacology, neuroscience) to – ultimately — individuals. Each individual is the product of a unique, lifelong sequence of social, cultural, economic, and psychological (as well as physical, chemical, biological, and genetic) influences. To this day, we don’t really know why some people get sick and others do not. To my mind, that makes medicine an application of science – like engineering – not a science in itself. Read more