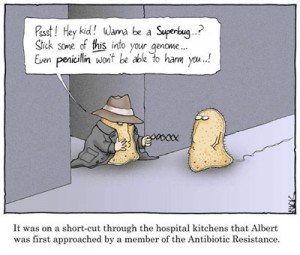

The Supreme Court recently decided, in the case of Bruesewitz v. Wyeth, that Wyeth Pharmaceuticals could not be held liable for injury to the Bruesewitz’ daughter (following a vaccination) because Wyeth was protected by the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act.

The Supreme Court recently decided, in the case of Bruesewitz v. Wyeth, that Wyeth Pharmaceuticals could not be held liable for injury to the Bruesewitz’ daughter (following a vaccination) because Wyeth was protected by the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act.

I was reading an article on this controversial issue in the NEJM when I was brought up short by the following sentence: (emphasis added)

Litigation such as the Bruesewitzes’ can help the FDA in its oversight function by revealing important and previously unknown information about product-related risks, especially during the postapproval period, and by deterring manufacturers from acting irresponsibly and engaging in business tactics aimed at increasing product sales at the expense of patient safety.

Now, I know corporations sometimes put profits before consumer safety (I once owned a Ford Pinto). And I know that, starting in the late 20th century, medicine became driven by corporate profits rather than traditional medical professionalism. (This is not to say that medical professionalism has disappeared. Merely that there has been a shift in values.) But it still troubles me to read a casual reference to profits being more important than patient safety. It’s an acknowledgment that such practices are an everyday occurrence, imperfectly dealt with by regulations and legislation, and are not a matter of what’s ethically right or wrong.

For-profit medicine drives increased use and costs

I believe medicine – which deals with life, death, pain, suffering, and disability – is not just another business like selling consumer goods. (See From MD to MBA: The business of primary care.) Other industries –automobiles, airlines — may need to consider life-threatening safety issues. But the primary focus of those industries is to sell a particular product or service, not to keep people alive and well. Read more