Megan McArdle spoke on antibiotic resistance at the Economic Bloggers Forum yesterday. McArdle is a journalists who writes for the The Atlantic, primarily on economics, finance, and government policy.

Megan McArdle spoke on antibiotic resistance at the Economic Bloggers Forum yesterday. McArdle is a journalists who writes for the The Atlantic, primarily on economics, finance, and government policy.

Her presentation, “Antibiotics: The world’s most broken market,” was interesting. Notice (in the video below) that she never questions the market-driven premise of pharmaceuticals – and by extension, the for-profit nature of medicine and health care. That’s not her politica/economic persuasion.

Here’s an excerpt from the talk where she discusses the patient/doctor end of the antibiotic resistance problem. What she says is already quite familiar. What’s interesting is her frank description of how doctors behave and how patients in turn regard doctors.

People love to get antibiotics. They go to their doctor and they’re like, “My kid has an earache. Give him antibiotics.” Now the doctor could say, “No we shouldn’t. We should wait and find out if it’s bacterial. Almost all ear infections are bacterial. Due to throat infections. Due to almost anything you can name. But to do that, the doctor has to sit down and deal with an angry patient who may pick up and leave their practice.

If you look at the way that the current insurance industry is organized, right, what do doctors need? They need volume. They get paid by volume. Reimbursements for primary care physicians, who are where a lot – by no means all – but where a lot these vaccines go through, are very low. They’ve made up for that, and you all know this, right. You go into your doctor, and the minute you start talking, your doctor exudes an almost visible — like — desire for you to leave now. So that they can go on to the next patient. So what do they do? They give antibiotics to patients to shut them up. It takes too much time to explain and the risk of losing the patient is high.

Where have all the unattractive people gone?

McArdle makes an interesting aside. She’s talking about how livestock are raised in overcrowded conditions, which leads to disease, so farmers feed them preemptive antibiotics. I hadn’t come across this idea before. (emphasis added)

Suppressing infection makes an animal grow faster, right. People are more attractive now than they used to be – they’re more symmetric, they’re taller – and in large part that’s because we’ve suppressed infection in young children.

She goes on to discuss some of the issues involved in getting pharmaceutical companies to develop desperately needed antibiotics. In particular, she describes the idea of creating a stockpile of new antibiotics that everyone will agree not to use for many years. (If we did use them, resistance would develop almost immediately.) This will mean some people (thousands? tens of thousands?) will die during the waiting period, when they could have lived. (Good luck on that one.) Someone (the government? foundations?) must agree to pay the pharmaceutical companies for all those years of waiting. And the US – for various reasons – will have to do this first.

Here’s the video:

Imagine medicine without surgery

An excellent book that discusses why pharmaceutical companies no longer produce new antibiotics – including problems of government regulation — is Brad Spellberg’s Rising Plague: The Global Threat from Deadly Bacteria and Our Dwindling Arsenal to Fight Them.

One of the things Spellberg discusses is that without new antibiotics, many aspects of the practice of medicine will change. Surgeries where there is an increased risk of infection – abdominal surgery, for example, or any lengthy, complicated surgery – would no longer be feasible. Chemotherapy, which wipes out the immune system, would be totally inadvisable. Transplants could no longer be performed. Intensive care is only possible because there are effective antibiotics. The chances of surviving burns, automobile accidents, and battlefield injuries would be greatly reduced.

In contrast to Spellberg’s serious, almost academic approach to the subject, The Economist had a recent article on antibiotic resistance that takes a rather cavalier attitude. “There are good reasons to hope that the extreme threat of a resistant epidemic will never come to pass. … Even so, the lesser problems of resistance continue to gnaw away at medicine.” Lesser problems like people dying, mainly children, the elderly, cancer patients, and those with HIV.

The cost of antibiotic resistance in the US is between $17 billion and $26 billion, says The Economist, but “America is rich, and can afford this.”

Also according to The Economist, it’s only “discretionary” surgery that would be at risk. “If resistant strains raise it [antibiotic resistance] to even 5%, let alone 10%, a lot of orthopaedic surgery, cataract replacements and other discretionary but life-enhancing procedures would simply stop. That would not be the end of the world.” Would that include cosmetic surgery, I wonder?

To keep up with information on antibiotic resistance, I recommend the excellent journalist Maryn McKenna (not to be confused with Megan McArdle), author of Superbug: The Fatal Menace of MRSA. McKenna blogs at Wired, and you can follow her on Twitter @marynmck.

Related posts:

Why are there no new antibiotics?

Links of interest: Can honey combat MRSA?

Links of interest: Antibiotic resistance

Overuse of antibiotics: Follow the money (part 1)

Overuse of antibiotics: A remote study (part 2)

Antibiotic resistance genes in soil microbes

Do houseflies spread antibiotic resistance?

Global challenge: 10 new antibiotics by 2020

Gonorrhea bacteria: The next superbug?

A brief history of antibiotics

Resources:

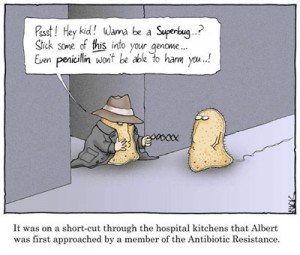

Image: World of Biology Wikispaces

Megan McArdle, Presentation at Economic Bloggers Forum 2011, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, April 1, 2011

Brad Spellberg, Rising Plague: The Global Threat from Deadly Bacteria and Our Dwindling Arsenal to Fight Them

The spread of superbugs: What can be done about the rising risk of antibiotic resistance?, The Economist, March 31, 2011

Maryn McKenna, Superbug: The Fatal Menace of MRSA

I watch McArdle’s video yesterday plus I read other articles on antibiotic resistance. Today I suddenly realized that with just a small rise in the percentage of surgery patients developing an antibiotic resistant infection and the high rate of C-sections will become a thing of the past.

So true. C-sections and a lot of other things. Let’s hope it never gets that bad. There are some promising developments, such as the use of nanotechnology — a new way of fighting bacteria. See http://bit.ly/eTcQfk

Thanks for commenting, Duncan.