Jill Lepore has an article in a recent New Yorker called The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong. Her target is Clayton M. Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma and, specifically, disruptive innovation. As usual with Lepore, her essay is personable and well-argued. What I liked most about it, though, was its brief discussion of how unfortunate it is that professions such as higher education and medicine are being privatized (if they’re not already) and administered to maximize efficiency, making profits more important than students or patients. (emphasis added)

Jill Lepore has an article in a recent New Yorker called The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong. Her target is Clayton M. Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma and, specifically, disruptive innovation. As usual with Lepore, her essay is personable and well-argued. What I liked most about it, though, was its brief discussion of how unfortunate it is that professions such as higher education and medicine are being privatized (if they’re not already) and administered to maximize efficiency, making profits more important than students or patients. (emphasis added)

Disruptive innovation as an explanation for how change happens is everywhere. Ideas that come from business schools are exceptionally well marketed. Faith in disruption is the best illustration, and the worst case, of a larger historical transformation having to do with secularization, and what happens when the invisible hand replaces the hand of God as explanation and justification. Innovation and disruption are ideas that originated in the arena of business but which have since been applied to arenas whose values and goals are remote from the values and goals of business. People aren’t disk drives. Public schools, colleges and universities, churches, museums, and many hospitals, all of which have been subjected to disruptive innovation, have revenues and expenses and infrastructures, but they aren’t industries in the same way that manufacturers of hard-disk drives or truck engines or drygoods are industries. Journalism isn’t an industry in that sense, either.

Doctors have obligations to their patients, teachers to their students, pastors to their congregations, curators to the public, and journalists to their readers—obligations that lie outside the realm of earnings, and are fundamentally different from the obligations that a business executive has to employees, partners, and investors.

Where did the idea that there’s no difference between manufacturing products, educating students, and treating patients originate? Jeff Madrick, in Age of Greed, summarizes Milton Friedman’s 1962 classic, Capitalism and Freedom, as follows: (emphasis added)

The central theme of the essays was that free markets not only can solve most of the problems of producing and distributing goods and services but also can solve most of the nation’s social problems as efficiently as possible. Boiled down, Friedman proposed that most social goods, including secondary schooling, healthcare, and retirement savings, were no different than a box of cornflakes, a Buick, or banking.

Lepore’s objection to this assumption seems perfectly obvious and sensible to me, yet to think so these days is to be in the minority. I gather there’s a great deal of soul searching going on lately about why what used to be called “the Left” is devoid of a substantial and meaningful challenge to the prevailing economic and political status quo. The general consensus seems to be that the bad guys (in my book) have won and the good guys either can’t seem to pick themselves up off the floor or — worse — they’ve been co-opted.

I like to read about these ideas, but I’m too much of a novice to actually discuss them myself. For now, I’ll just keep reading, hoping to come across something that provides a glimmer of optimism.

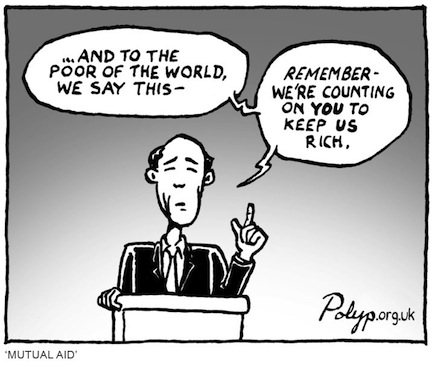

Why the rich don’t care about the poor

As I read, I’m also looking for explanations of why current economic and political agendas have no objection to inequality, poverty, unemployment, and the stagnating wages of the middle class. You might think, after all, that corporate interests would favor the maintenance of purchasing power.

Economist and New Yorker columnist James Surowiecki recently made an excellent point that speaks to this. His article is called Moaning Moguls. It begins with a description of those super-rich individuals who complain that they’re being criticized and who feel sorry for themselves as a result. Quoting Mark Mizruchi: “These guys think, We’re the job creators, we keep the markets running, and yet the public doesn’t like us. How can that be?”

After describing the historical argument that Mizruchi makes in his book The Fracturing of the American Corporate Elite, Surowiecki writes: (emphasis added)

If today’s corporate kvetchers are more concerned with the state of their egos than with the state of the nation, it’s in part because their own fortunes aren’t tied to those of the nation the way they once were. In the postwar years, American companies depended largely on American consumers. Globalization has changed that—foreign sales account for almost half the revenue of the S&P 500—as has the rise of financial services (where the most important clients are the wealthy and other corporations). The well-being of the American middle class just doesn’t matter as much to companies’ bottom lines. …

Moguls complain about their feelings because that’s all anyone can really threaten.

An excellent point that I don’t hear often enough.

Related posts:

Teaching the oligarchy not to care

Two children visit their doctors: Social class in the USA

For U.S. health care, some are more equal than others

A more equitable future? US reveals its true intentions

It’s cheaper to let the sick die

The new economic reality

Health care in America: You get what you deserve

Life expectancy of the rich and the poor

This mess we’re in – Part 3

Image source: Engaging Justice

Resources:

Jill Lepore, The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong, The New Yorker, June 23, 2014

James Surowiecki, Moaning Moguls, The New Yorker, July 7, 2014

Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma: The Revolutionary Book That Will Change the Way You Do Business

Jeff Madrick, Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

Mark Mizruchi, The Fracturing of the American Corporate Elite

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.