The August issue of Social History of Medicine contains eight original articles:

- Late 19th/early 20th century food adulteration in an increasingly industrialized and globalized world and the search for safety standards

- The shift in cancer education in the 1950s, no longer downplaying post-operative recovery

- The 20th century shift in British veterinary medicine towards small animals (dogs, cats), as the need to attend to horses declined (open access)

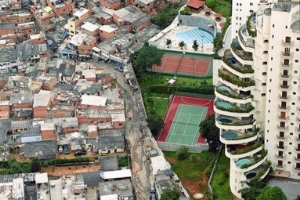

- How complaints about the quality of London drinking water in the 18th century reflected the new popularity of bathing for health and social attitudes towards bathers from the lower classes

- A re-evaluation of the prevalence of venereal disease at the time of the World War I (open access)

- How quacks preyed on people with hearing loss in mid-19th century Britain

- How the 1975 TV play, ‘Through the Night,’ portraying what it was like to experience breast cancer treatment, registered with medical professionals and activists who complained of ‘the machinery of authoritarian care’ (open access)

- Did Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich actually develop an animal model of experimental research?

There are also a large number of book reviews, including:

- Writing History in the Age of Biomedicine by Roger Cooter with Claudia Stein

- Emotions and Health, 1200–1700 by Elena Carrera (ed.)

- The Age of Stress: Science and the Search for Stability by Mark Jackson

- Before Bioethics: A History of American Medical Ethics from the Colonial Period to the Bioethics Revolution by Robert Baker